Painting and pain in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections

With the collaboration of

Author: María Martín Sánchez

“Pain is not beautiful; it’s atrocious. It pits us against our own human condition, our finiteness, and only then can we to discern –amidst the horror– a shimmer of light. We tether ourselves to it with a rope and cast it off to avoid getting lost in our terrible forest of shadows, and there, all of a sudden, amid a clearing, beauty –so red– awaited us surrounded by women Masters, friends, companions, sisters…”

Ana de Castro., Rojo-Dolor. Anthology of women poets on pain (prologue), 2021.

Pain has been with us since the dawn of time. Associated with illness or loss, with certain experiences and life lessons, in a physical, emotional, or spiritual sense; pain is one of the major emotions human beings are able to feel, regardless of their age, origin or culture.

Philosophers, thinkers, doctors, scientists from various fields; but also, musicians, poets, and naturally painters, have strived to decipher, understand, and apprehend it; to express through the senses and artistic language, their vision of pain.

Art as a witness of its time, as a window into different periods and moments, enables us to trace the views different societies have held in regard to themes so apparently removed from art as illness or pain. We invite you on a journey to contemplate how people from other centuries regarded and expressed pain; how the artwork that captures their concerns and ways of thinking continues to move us and help us to evoke certain experiences; how our relationship and current experience with pain, has powerful connections to the past and such ties can help us to build a better future.

Starts on the second floor.

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

The Virgin and Child enthroned with Saints Dominic and Martin, and two angels

Pain and its reflection in art.

Factors related to pain: spirituality.

Our relationship to pain was, for centuries, imbued with religious thought. Its origin and characteristics were interpreted as divine punishment or possession by evil spirits; the very expression of pain was underscored by Christian iconography. Both its physical as well as emotional and spiritual aspects were the subject of artistic creation.

For centuries pain was experienced more than it was studied: rites, spells and natural remedies were the means to subdue it. Egyptian and Chinese medicine attempted to decipher the origin and behavior of pain. But it was the Greek and Roman philosophers who spent the most time pondering the nature of pain beyond myth and religion. Hippocrates (460-370 BC), the father of medicine, formulated the theory of the four humors, according to which good health resulted from a balance between bile (yellow or black), blood and phlegm; and illness arose due to a lack or excess of any of these elements. Alcmaeon of Croton and Aristotle debated whether the brain or the heart was the core of all vital functions, and thus also the source of pain.

After them, Roman doctors such as Dioscorides, Celsus or Galen of Pergamon, took it upon themselves to study pain, its nature and origin, its relationship to sensory nerves and motors; and they tried to alleviate its effects on the human body by using analgesics such as mandrake wine. They crafted complex theories about sensations to explain how the latter stemmed from nervous system, and they described pain as an unpleasant sensation captured by all the senses, whose purpose was to alert the body, and which was also quite useful as a diagnostic tool.

Medieval Europe interpreted pain as punishment for human sins. Painkillers symbolized an undeserved escape from an experience intended to redeem man. Only a life inspired by Christ, prayer, sacrifice, and dedication could lighten the load. In this sense, spirituality became an emotional refuge.

This panel of the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Dominic and Martin, and Two Angels depicts a Hodegetria virgin as a mother who recognizes her child’s destiny, accepts it, and holds him up as a model for confronting death, pain, and suffering. Despite her apparent inexpressiveness, she subtly manifests her emotions: she looks directly at us, revealing her cause for concern. She inclines her head slightly toward her child and holds him in a protective and motherly embrace, while gesturing towards him as a role model to be followed when confronting sacrifice and death.

The Christ child, in all his wisdom, recognizes how his mother intercedes on behalf of humanity. He regards and blesses her, and through his gesture, also blesses all those who remain faithful to his teachings; only they shall obtain his protection and forgiveness.

At their feet appear Saint Dominic of Guzmán and Saint Martin. The former, who founded one of the most important Christian orders, receives a rosary from the Virgin, an effective tool for tackling sickness, pain, and physical suffering. The latter, a Roman soldier converted to Christianity who later became the bishop of Tours, was another of the most popular saints during the Middle Ages, known for curing victims of leprosy, one of the most excruciating diseases of the period.

For centuries, the Virgin and the saints were considered humanity’s allies for confronting suffering, given their ability to overcome and relieve pain. Presently, all models for tackling pain from a nursing perspective recognize spirituality as a parameter related to pain. At Pain Units, attention is paid, in addition to physical exercise or good posture, to the influence of cognitive reactions to chronic pain. Our internal dialogue influences our state of mind, just as the latter affects our lived experience and relationship with pain. Spirituality today continues to play an essential role for many sick people with chronic pain regardless of the new medical techniques used to handle it.

Saints Cosmas, Damian and Pantaleon

Professionals in the care and treatment of pain: doctors.

Doctors have played an essential role throughout history in caring for and improving the quality of life for the pain afflicted. Among the most important physicians mentioned in the chronicles we find Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian.

Both practiced in Egea in the 3rd century BC, until they were jailed and tortured by the governor of Cilicia. Notoriety from their miracles –which included complex surgical operations– reached Rome, where they were recognized as the patron saints of medicine, surgery, and pharmacists.

Saint Pantaleon of Nicomedia –he who took pity on all– acted as doctor to the Emperor Galerius Maximianus. Devoted to aiding and curing the poor and the sick, he healed paralyzed people, restored sight to the blind and worked all sorts of miracles. Today he is still considered as the patron saint of the sick.

They are depicted as professional doctors, holding their books and study materials, ointment jars, dyes and oils, and a knife, a tool used as a scalpel for practicing surgery by surgeons-barbers-bleeders.

Although the first college of medicine dates back to the 9th century (Scuola medica of Salerno), it was not until the 15th century that this science was transformed into a technical discipline. Training by oral tradition from master to apprentice was gradually abandoned; institutions and official studies were created and certified doctors underwent examinations regulating their training and professional activity.

Thanks to direct research through postmortem dissections, there was greater awareness of the structure and functioning of the human body. Along with the anatomists, the best artists of the period documented and recorded the new discoveries; despite the issues raised by the Church’s unfavorable opinion of this practice. Furthermore, phytotherapy, which flourished in monasteries, enjoyed greater resources thanks to translations from ancient Arabic, Greek and Roman texts. Compounds used today in pharmacology, such as salicylic acid, were already in use back then. In spite of the new scientific spirit, pain management continued to be based more on religion and the notion that such pain was pleasing to God.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, significant progress was made in anatomy and the physiology of the central nervous system. Research was carried out on the exact source, scope, spread and rate of pain. New inroads were made into the causes of disease; pain began to be considered a physiological phenomenon with emotional implications.

The analgesic properties of gases such as nitrous oxide was discovered, which would lead –by the mid-20th century– to the use of ether. Morphine, codeine, and opiates began to be applied to alleviate pain. Also crucial were the advent of the syringe (Wood), the needle (Rynd), spinal anesthesia (Bier) and X-rays.

Pain gradually lost its mystical connotations and ceased to be a matter of faith handled by religious institutions, to become researched and treated by science. By the 1970s, pain began to be considered a chronic disease, and the first units appeared focused specifically on its study and treatment.

Many were the changes medicine underwent since this 15th century depiction was painted, but thanks to this type of visual testimony we are able to know firsthand the tools, techniques and methods devoted to understanding and tackling processes of pain, as well as the value society placed on the latter.

For centuries, medical professionals –and subsequently, psychologists and nurses– have strived to treat sickness and pain. They have researched and treated all sorts of conditions, helped to prevent ailments, and helped society as a whole by attempting to improve quality of life and by providing not only treatment, but information, support, and consolation.

The Crucifixion

Pain as reflected in art.

Pain, martyrdom, and religious sentiment.

Caregivers of the pain afflicted.

The Crucifixion of Christ has been one of the most depicted and sought after pain iconographies to be commissioned by all types of buyers.

Through this scene, the suffering of the sacred characters was relieved, and empathy was shown for their plight.

Throughout the Middle Ages, artists focused more on moral messages than the emotions of the characters involved, who display inexpressive faces, gazes and hands aimed more at communicating their suffering than expressing it. As of the year 1350 we would witness a profound shift in expression: the devastating black plague epidemics promoted religion as a source of protection and refuge. A new spiritual trend, Devotio Moderna, would develop pious practices based on humility, obedience, and the simple life. It had a decisive impact on Christian iconography.

Gerard David, a Flemish painter of Dutch origin, forged a personal style based on detail, expressiveness, and precious refinement. He worked in Bruges and Antwerp, drawing inspiration from the great Flemish masters who preceded him, and from Italian art. His Flemish training is decisive in the way he approaches a theme such as the Crucifixion. To express pain and cruelty, he does not resort to morbid or gruesome imagery, but rather to the characters’ body language.

His Christ crucified reflects suffering that is more symbolic than physical. His serene depiction speaks to Christ’s divine and perfect nature; only his twisted body reveals some tension. The figures of those who witnessed his suffering are the ones who reflect his pain. The Virgin appears faint, broken, limp; experiencing a symbolic demise that ties her to her son’s own death. She is so devastated by her anguish that she needs to be propped up. This iconography would be criticized during the Renaissance for questioning divine nature, given her inability to control her suffering.

Saint John and the Magdalen experience their pain in a more introspective and subdued manner. They attend to the Virgin as tears roll down their cheeks. Providing support in mourning as in pain constitutes a challenge for all. Sickness, pain, or the loss of a loved one leaves no one indifferent. The company of others, active listening, being present, tenderness, support; are positive ways of helping that enable us to endure pain differently from how we would on our own. Pain is not only a problem for the person suffering, but also for their immediate environment.

María Cleofás and María Salomé refer us to ancient funeral practices and rituals, such as the weeping mourners: their wailing, furrowed brow, squinting eyes, frowning lips or elevated arms and open hands, are not only a physical but also a social and cultural response. Many of these customs were reflected in the painting.

On the right-hand side of the piece: characters with completely opposite reactions and unpleasant faces who stand for evil, heresy, and moral corruption.

Pain is a universal human feeling, but the way it is expressed varies by culture, period, and context. The way we communicate things; our gestures, tone, how we modulate for each patient, is not always akin to the attending professionals’ own cultural narrative, based on the information offered by the patient or the bereaved. This can influence their diagnosis and treatment.

In some cultures, emotions are not overtly manifested. Drawing attention to pain or even discussing it can be considered offensive or a sign of weakness. Being aware of the diverse ways in which pain is expressed can help to alleviate it properly, effectively, and conscientiously in patients.

The Risen Christ

Pain as reflected in art.

Pain, martyrdom, and religious suffering.

The figure of Christ, particularly in Passion iconography, is, for European culture, one of the great models of pain. His figure not only depicts pain as a trial and as destiny, but his artistic image has shaped a particular way of visualizing, recognizing and representing sickness, suffering and even the image of the bereaved.

From a Judeo-Christian cultural perspective, the Passion of Jesus can be considered a model for living and acceptance by the faithful.

Extracting beauty from harsh conditions enabled a person to approach the painful process as a learning path; knowing that behind all suffering lies a destiny and a purpose gave meaning to sickness: the fulfillment of divine designs, resurrection, and attainment of Paradise.

In art as in thought, beauty and imperfection have been intertwined on many occasions. The Greek philosophers did not believe the world was necessarily beautiful and perfect in its totality. From mythology to the Pythagorean or Platonic theories, sickness and death are discussed as a counterpoint to a perfect and balanced world created by the gods.

For Christianity, the universe was beautiful and full of meaning and a reason to exist, since it was divinely inspired. Total and perfect beauty redeemed the presence of ugliness and evil, of sickness, suffering and death; it was all part of an equilibrium.

That dual nature is clearly visible in the figure of the suffering Christ: he was man and a divine being; an imperfect body and spirit. His sacrifice was a metaphor of how to accept the harshness of life; how to manage pain and overcome it and emerge renewed from the experience. Christ’s image in the Passion series is, most importantly, a human image. He could not be depicted according to the classical ideal and cannon: his pain had to be evident in order to comprehend the scope of his sacrifice, the value of his experience and the glory promised through his suffering.

Bramantino (1465-1530), was a renown painter and Italian architect from the Renaissance. His influences included Bramante, whom he met during his youth and from whose Christ at the Column (Pinacoteca de Brera, Milan), this piece draws its inspiration. Characterized by a complex and eclectic style, he is considered to be one of the most relevant artists of his time. He worked in Rome and Milan, at the service of powerful men such as Pope Julius II or Francesco María Sforza, duke of Milan.

The piece at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, is without a doubt, one of his most famous and striking paintings. Bramantino depicts the Risen Christ using a particular esthetic and approach, eschewing medieval idealization and the triumphant Christs represented by painters like Raphael. His Christ speaks more to the scientific-humanistic interest in the study of the human body than to a spiritual purpose. Many artists of the Renaissance, influenced by 15th century naturalism, devoted quite a bit of time to the study of anatomy, and even resorted to dissections. Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer, and Leonardo da Vinci sought to research human anatomy on their own, going beyond the treatises, to better understand the body and how it functioned; a theme passionately embraced by the artistic world, but whose presence needed to be justified in artwork through characters or specific stories such as this one.

Half-dressed, the cloth reveals part of his anatomy. He appears bearing his wounds, his moist and pale skin, his emaciated body, high cheekbones, gaunt face, reddened eyes. Every physical detail is a sign of pain, a hint to help the viewer recognize the mark of suffering. In the background, an almost spectral, nocturnal landscape, illuminated only by the moon. It is the portrayal of a man who has undergone a painful experience and managed to escape from it yet is still affected by the process he endured.

Thanks to studies by painters like Bramantino, greater awareness of the human body was achieved along with the cataloguing of diseases, physical ailments, medical issues, and bodily symptoms, which was analyzed through the eyes and brushes of the artists. This scientific iconography of the pain afflicted left its mark on artists from the past, for example, during the Romantic period and continued into the present, thus helping us to detect discomfort and pain in both ourselves and those around us.

The awareness, approach to, and treatment for pain and those who suffer from it has changed; but the sensory and emotional experience connects us with people from all periods.

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

Invisible and silenced pain.

Caregivers for the pain afflicted.

Factors related to pain: spirituality.

Art and improving quality of life.

On October 7th, 1488, Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, was dying, pregnant with her second child. Her family commissioned Domenico Ghirlandaio with this posthumous portrait. He was one of the most renown painters of the Italian Renaissance. The painting thus became not only a display of beauty, but a keepsake for her loved ones, who could then remember her and attempt to channel the pain caused by her loss.

Born in Florence into a family of wealthy wool merchants tied to the Guelph faction, Giovanna was wed to young Lorenzo Tornabuoni, a blood relation of the Medici, enemies of the Albizzi. Their marriage symbolized a political rapprochement to ease tensions between the families. The wedding was celebrated in 1486, when the young girl was 18 years old. Her first child, Giovannino, was born in 1487. Towards the end of her second pregnancy, one year later, complications ensued, and both Giovanna and the child that was on the way died.

We do not know the specific causes of her death, but we do know that womens’ health care was influenced by eminently male-dominated science, which approached healthcare with a bias against women and led to their pain being deemed pathological and to the stigmatization of womens’ experiences. Her condition was seen as something normal and natural that needed to be stoically endured. Her pain was overstated and exaggerated and associated with hysteria.

All of this, in addition to the fact that society perceived women as inferior beings, or the fact that it was considered indecorous for a man to examine female patients, led to many women not being treated properly and to their cases not being attended by certified physicians. Their healthcare was often left, on many occasions, in the hands of female witch doctors and healers. These were women with practical training and considerable knowledge of phytotherapy who not only treated women and children (within womens’ traditional role of assisting with pregnancies and gynecological issues); but also took on general medical situations for all sorts of patients or prepared therapeutic remedies and even handled minor surgeries. But they were gradually relegated and excluded from academic circles, pushed out of healthcare, and forbidden from practicing procedures.

In the absence of professionals interested in properly treating patients, rituals and amulets were the means used to try to cast off illness, minimize pain and ensure survival. Ointments, relics, religious imagery, and all sorts of talismans, attempted to expel the negative forces that might endanger life. Also red coral jewels, such as ones we see in the portrait, were considered to offer protection.

The prayer book, in addition to emphasizing the deceased’s piety, was another instrument of divine protection. Rich and powerful citizens were particularly vulnerable to this sort of attack, given that their lifestyle aroused envy and the evil eye. This portrait, which must have been commissioned the same year Giovanna passed away, attempted to use the divine power of art to make her, somehow, more present. The living and the dead remained connected through painting, keepsakes, and peoples’ recollections, all of which were capable of transcending death. Art was a spiritual refuge; the portrait served to restore the deceased. Following Giovanna’s death, even after her husband remarried, the piece hung in his Chambers, given that, as the epigram by Martial that appears on the panel states, the image had captured the likeness and soul of the young woman.

Many professionals currently defend that womens’ health is not necessarily related to only biological differences but also closely tied to a biased perspective that has discredited womens’ ailments and experiences, and overlooked social, economic, and cultural circumstances affecting female patients and their illnesses. The greater prevalence of pain in women, the influence of their mental burden or their type of work on the course of their illnesses, or the tendency to medicalize instead of preventing illness through medical techniques, requires a profound examination that is currently already underway. Listening, understanding, and providing support to those in pain, are also vitally important medical procedures.

Portrait of the Emperor Charles V

Professionals in the care and treatment of pain: doctors.

Pain as a universal feeling.

Invisible and silenced pain: acute and chronic pain.

One of the best-known cases of chronic pain in history, was that of Emperor Charles V. In addition to being asthmatic, diabetic and having suffered from malaria, this famous patient endured a life of terrible gout attacks and severe arthritis that decisively affected his reign. His case proves that, regardless of factors such as age, sex or socioeconomic status, chronic pain affects us all.

Thanks to modern paleopathological techniques, scientists have analyzed a mummified finger of the emperor. His biopsy and X-rays showed the erosion of the bone due to urate crystals, typical of gout, which confirmed the severity of Charles V’s articulation issues mentioned in the chronicles.

For centuries this was one of the most prevalent diseases in the clinical presentation of various figures such as Henry VIII of England or Charlemagne.

It was known that gout, a common and complex form of arthritis, caused Charles V to suffer from severe physical incapacity since the age of 28. His doctors urged him to follow a strict diet, but the emperor, quite the consumer of red meat and game, as well as wine and beer, refused to modify his eating habits. He was a difficult patient and failed to follow diets or doctors’ advice.

Diplomats like Marino Cavalli or Guillaume van Male, mentioned the emperor’s illness in their correspondence. He needed a special chair to get around. He would seek comfort by placing cushions under his feet to minimize the pain while seated. One of his trusted ironsmiths, Desiderius Helmschmid, adapted various suits of armor for him using more flexible articulations to make him more comfortable and reduce his suffering.

His chronic pain and physical suffering influenced the decisions he made and affected the future of Europe, by forcing him to postpone certain military activities and conquests. His illness may have led to his abdication in 1556 and withdrawal to the Monastery at Yuste. The move did not manage to improve his habits: he continued to partake of hearty and copious meals and all sorts of feasts. He was only 58 years old when he died, but he had the appearance of an old man.

From all the chronicles and references to the emperor’s health, the most important ones are from his doctor, Andrés de Vesalio, one of the great innovators in medicine, author of the famous treatise on anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica. Acting as the imperial physician since 1544, he treated Charles V’s malaria and gout; cured his syphilis, detected his cavities, and saved the son of Philip II, Sir Carlos, from almost certain death following a blow to the head. In 1545, he treated Charles V’s severe gout attack by applying Chinese root or sarsaparilla. Having already been used by Dioscorides, it was usually brewed as tea. It was not particularly tasty but could induce vomit and alleviate the pain caused by gout, probably due to its diuretic properties. A

nother of the ills Charles V suffered from was his pronounced prognathism, which in his case was a hereditary condition. While today it is a problem that can be solved through orthodontics or surgery, back then a thick beard was one of the means used to disguise his prominent chin.

Although the emperor generally took his illnesses and pain in stride and good humor, we know that his jaw forced him to always appear with his mouth half-open; he articulated speech poorly and the chewing and swallowing of food was hard for him. The shame he felt when others watched him struggle to chew his food led to him eating alone, so that no one could contemplate his predicament.

Nevertheless, he transformed his peculiar jaw into a symbol of power. Northern masters like Seisseneger, Christoph Amberger or Cranach, emphasized the prominence of his jaw as a distinctive feature of his lineage. Cranach, a distinguished representative of the German Renaissance, painted several portraits of Charles V over the course of his life. They were realistic and straightforward portraits, far-removed from the artistic license and idealization typical of Italian painters like Titian. In his portraits, Cranach reproduces the marked prognathism the emperor tried to conceal under his beard, with the protruding lower lip, the elongated face, large nose, and slightly hunchback-shaped back, visible under his rich fleece garments. The only element that appears to reference his royal condition is the emblem of the Order of the Golden Fleece hanging from his neck-chain.

The Death of Hyacinthus

Caregivers for the pain afflicted.

Art and improving quality of life.

Myths were originally not only answers to the major questions posed by humanity but also models of how to live or act when confronted with certain experiences. The story of Apollo and Hyacinth is one of the most explicit in terms of how to live with and manage pain.

According to the classical story in Ovid’s Metamorphosis (Book X), the god Apollo lost his mortal love –Hyacinth, an Etruscan prince– in a sporting competition, while both lovers were throwing a disc. While striving to display his physical strength and command of athletics, Apollo hurled the object so vehemently that his young lover –in an attempt to not disappoint Apollo while showing off his agility– was killed by a deadly blow to the head.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770) was one of the most skilled and celebrated painters from the Venetian school of the 18th century. A splendid illustrator and unrivaled alfresco painter, he worked for the cream of the crop of European nobility. Around 1752, the German baron Wilhelm Friedrich Schaumburg-Lippe contacted him to discuss commissioning a piece. Tiepolo was in Wurzburg, working for Prince-Bishop Carl Philipp von Greiffenclau.

Schaumburg-Lippe was a 28-year-old young man, born in London in 1724, whose father held a prominent position at the court of George I and George II from Great Britain and Ireland . He had studied in Geneva and Leyden, was fluent in several languages and an art lover. But this commission was not only motivated by esthetic or artistic considerations, but rather others of a more personal nature: the count had various male lovers. In one of his letters, he spoke of his “beloved Festetics, the other half of myself,” a young Hungarian who captivated him. He was also involved in a complex love triangle with a female ballet dancer and the male director of a Spanish orchestra, whom his father nicknamed “your friend Apollo.” When the musician died in 1751, William of Schaumburg-Lippe returned to German territory. That same year, Tiepolo received the commission.

In order to execute this piece, which is bursting with light, brilliant colors, beautiful and idealized characters and masterful theatricality, the painter drew inspiration from the translation of The Metamorphosis by Giovanni Andrea dell’ Anguillara (1561); in which the death of young Hyacinth is narrated as an episode that transpired during a heated match of pallacorda. The palla, a sport in fashion since the Renaissance, played by Cosimo de’Medici or Alphonse II d’ Este, was reaching its peak thanks to its physical benefits and esthetic value linked to grace and elegance. It was, nevertheless, a risky sport since the balls used could injure or even kill a player. Count William was an exceptional player who would only forego a match for his Festetics, who had “preference before all the kings in the world.”

Hyacinth, whatever his metaphorical identity may be, lies stretched out on the floor, covered with a skirt and a long strap like the ones players wore to protect their gut from the impact of the ball and potential concussions. Instead of the disc that caused his death, we find two tennis rackets; one on the ground quite close to the flower that bloomed from his blood. The sculpture of a satyr regards the god and his lover with a ruthless smirk on his face.

Apollo, draped in a lavish and rich fabric in classical style, expresses his pain with a striking gesture. Despondent, he leans over to bid farewell to his lover. As the favorite deity of the Italian painter, he was depicted numerous times over the course of the artist’s career. He embodied beauty and youth but was also related to pain through his lovers’ many deaths and punishments.

Tiepolo captured a tragic and real episode and blended it with myth. The divine tale intersected with lived experiences and emotions; and helped to bear the suffering caused by the loss of a loved one by bringing him into the present. Artwork was thus transformed into a balm for pain.

El tío Paquete

The artist’s own pain Pain and trauma.

Factors related to pain: work.

Tío Paquete was a very well-known blind man in Madrid, who used to frequent the area around the church of San Felipe el Real and enliven the day of passers-by through song and guitar-playing, in exchange for a few coins. A popular and bubbly character, he inspired the artist, a passionate follower and connoisseur of the music of the period and artists such as Rubens, Teniers, George de Latour and Jacques Callot, who had already depicted blind traveling musicians as a metaphor for the senses and esthetic pleasure and as a means of critically discussing the harshness of the world and its inhabitants.

Goya portrays Tío Paquete without the slightest bit of idealization, starkly and straightforwardly. The hollowed eyes, which intensify his disability; his gaping, toothless, wide-open mouth. He cackles shamelessly, sarcastically, and excessively. His big round face, tilted to one side, increases the viewer’s sense of unease. Drama and comedy are blended in a character who appears to have seen it all, as if he were able to see through his blindness, the true nature of the world.

In 1819, Goya suffered a relapse of an illness that had begun in 1792, at the age of 46. He then began to have difficulty keeping his balance and seeing. Hallucinations, severe headaches, and the loss of hearing in both ears gradually intensified. He slowly turned deaf. He even tried to cure himself using an electric machine that had been invented by the German physicist Otto von Guericke in 1663, one of the first known examples of electrotherapy.

These and other health crises help to explain his medical issues ranging from syphilis to malaria. He also suffered from saturnism, a type of poisoning caused by daily handling of the white lead used to prime paintings, which can cause colic, deafness, and terrible pains.

Hippocrates, in his Theory of four humors, already spoke about the damaging effects of this metal. Centuries later, Bernardino Ramazzini described in his Treatise of the Diseases of Tradesmen, symptoms including trembling hands and articulations, convulsions, intense stomach pain and melancholy, which affected painters. Cooking and medicine made it possible, through diets, bleeding and bloodletting, as well as Hellebore consumption, to keep symptoms in check.

The theory of four humors, which would still be in force until the mid-20th century, established a series of temperaments based on how much of a particular fluid an individual had in their body. Melancholics or those born under the sign of Saturn, were associated with the night, black or grayish colors, bats, melancholy, and artistic sensibilities.

For centuries, Goya’s peculiar creativity and personality led to his illness being associated with this model. Today the most plausible hypothesis points to Susac’s syndrome, which is characterized precisely by hallucinations, paralysis, and a loss of hearing.

However, his physical condition definitely affected his state of mind and emotions, both of which were influenced by a particular context. From 1819 to 1823, Goya created his Black Paintings, a testament to the war period, to horror and despair; but also, to disease, old age, and the perception that he was no longer the man he had once been; his physical pain and emotional trauma had transformed him into another man. He avoided embellishments and concessions, and through his impassioned technique and expressive style, Goya’s artwork reflects the worldview of a lucid man intent upon leaving a direct testament of reality. It is a personal undertaking, much like a cathartic act aimed at physical and emotional pain management. During those same years, using the same technique and pictorial esthetic, he also painted El Tío Paquete.

Nowadays, in order to provide the best treatment, one must consider the biological, psychological, and social factors that play a role in pain. Only from a comprehensive perspective can one comprehend that chronic pain is a disabling disease that affects our everyday life, our activities and state of mind. Tackling both disease and pain from an accepting and life-affirming stance can make all the difference to the afflicted.

Continue on the first floor.

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland

Professionals in the care and treatment of pain: nurses.

Nursing has been vital to the preservation of the human species. Individual and group healthcare, support through pain and death; have existed since the dawn of civilization. From the intuition, observation and experience of shamans, witches or healers to the help and selfless charity fostered by Christianity; gradually, nursing would extend beyond the domestic realm, through altruism and vocation, to become a specialized profession.

Anonymous or well-known women –predominately– such as Marcela, Florence Nightingale, or Edith Cavell, marked the beginning of a trade in parallel with physicians without which it would be hard to imagine medicine today.

A deciding moment in the consolidation of nursing as a profession was World War I. Schools for officials arose and institutions such as the Professional Association of Nurses or the International Council of Nurses (USA) were created.

Shirley Williams, in The Great War and Modern Memory, speaks about the vital role played by nurses during the unfolding events. She unpacks the myth of the courteous nurse, dressed in her immaculate white suit; and reveals their exhausting work, and high degree of personal sacrifice; a dangerous pursuit in direct contact with the horror of combat, and often performed voluntarily by nurses from the VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment). Many of the women who took part in it belonged to aristocratic families, such as Millicent Fanny Saint Clair, duchess of Sutherland and a progressive lady from British high society who devoted all her time to collaborating with noble causes.

Shortly after the war broke out, Saint-Clair took doctors and nurses to France and Belgium, and organized transportation and equipment to set up hospitals and aid stations for victims. She traveled to France to put together an ambulance unit, and under the auspices of the French Red Cross, along with surgeon Oswald Gayer Morgan and eight other British nurses, she moved to Namur (Belgium), at summer’s end in 1914. Trapped by the German occupation, she and her nurses escaped in a dramatic journey she narrates in her autobiography, Six Weeks at the War.

In October of 1914, she returned to France to set up a hospital with 100 beds at Malo les Bains, near Dunkerque, which she later moved first to Bourbourg and then to Calais; and expanded using awnings lent to her by hotels in order to attend to the greatest number of injured victims.

The French artist, Victor Tardieu (1870-1937), met Millicent Sutherland at her field hospital. There he painted her offering medical aid to injured soldiers and collaborating in their care, pain management and recovery.

The tireless work she performed, along with her incalculable contribution to the injured and her intercession to save thousands of people, led to her being awarded the Cross of War and highly regarded by the Red Cross. Even the most distinguished officials of the British army paid tribute to the bravery, determination, and professionalism of these women, given the pressure they were under and the firm commitment they had shown.

None of this story is apparent in the marvelous portrait Sargent painted of the duchess of Sutherland in 1904. John Singer Sargent (Florence, 1856-London, 1925), an American painter trained in half the academies of Europe, moved his workshop to London in 1886. That was where Millicent Saint Clair commissioned him with her portrait, knowing full well that he was a controversial artist. The duchess was depicted in a radically different manner from Tardieu’s piece; but behind her beauty and elegance, one can catch a glimpse of her energetic demeanor and powerful gaze, typical of a personality with the highest degree of valor, commitment, and service to others.

Swaying Dancer (Dancer in Green)

Factors related to pain: habits.

Factors related to pain: work.

The artist’s own pain.

Care for the body and its connection to good health, has not always been an essential feature of society. As of the 19th century, the social hygiene movement would focus on the importance of health and began to consider illness as a social phenomenon affecting all aspects of human life.

Urban renewal in pursuit of greater public health standards was accompanied by the spread of therapeutic gymnastics, or new diets and the promotion of healthy habits that stressed which foods to prioritize and how to preserve them better or how to supplement them with tonics and restoratives.

Along with the new focus on caring for the body, came the notion of leisure and free time. Promenades in the open air or ocean and sunbathing; socializing, attending fine arts exhibitions or enjoying a good opera or ballet performance; were just as important as physical care. Paris, a center for the arts and European culture, fostered and disseminated activities typical of the new bon vivant. But far from being the city of light, it also harbored a less pleasant side.

Bars and nighttime cabarets had doctors on hand, given that the crudeness of some shows caused audience members to faint; workers exhausted by the long workdays in exchange for salaries that impacted their quality of life; workers exposed to harsh conditions in unhealthy spaces.

Swaying Dancer (1877) places us in the middle of a ballet performance, as if we were watching her dance live from a side balcony, contemplating her spinning through a pair of binoculars. Degas, a ballet lover who assiduously attended performances, sought through the dancers “to rediscover the movement of the Greeks,” and captured all that dynamism through his skillful technique. They appear to be cut off; we only see a piece of a leg, a bit of a tutu; other dancers, in the background, wait their turn or just finished their performance. The scenery is diffuse imagery; the pictorial space is not in the center, but rather a transitory, changing environment. The audacious torsion, the sprightly gesturing, are captured with fast, lively, and spontaneous movements; and great technical realism.

The dedication of the dancers painted on so many occasions by the artist, was absolute. They worked their bodies to the limit for the purpose of moving the audience with their pirouettes and impossible feats. Their most frequent injuries included sprains, tendinitis, and joint damage. The most feared were muscular fiber ruptures, since they kept them offstage for weeks and even months, with no work or salary; much like ankle ligament breakage and joint fractures of the metatarsal bones. Pain could not be treated by the means we use today; neither did surgical techniques and operations exist to minimize the impact of issues stemming from particular work methods.

Singers, portrayed by contemporary artists like Vuillard or Toulouse-Lautrec, also suffered from work-related ailments such as laryngitis, edemas from overworked throats or broken vocal cords.

Neither was the painter’s trade free from risks. Degas suffered from retinopathy, a degenerative disease of the retina that damaged his central vision. His vision was blurry, his sharpness of sight decreased, and sunlight caused him terrible pain; a terribly complicated situation for an impressionist painter, obsessed with light and color. The painter spoke for the first time about his “visual ailment” in 1880; he was particularly afraid of going blind and could only paint for a few hours, during which he labored haltingly and with great sadness, since the light was “intolerable”, even though he would attempt to keep his eye “half-open enough to see until he was satisfied.”

His eye condition was closely tied to his new painting style. His sharpness, detail and refinement gradually gave way to greater expressiveness. He traced irregularly shaped bodies and put forms together using dabs or patches of overlapping colors. Nothing in Degas’ correspondence indicates that he was consciously attempting to change styles, to be more expressionist or abstract. He managed to prolong his passion despite being deprived of his most important work tool.

Renoir was another Impressionist painter whose artistic conception and design was influenced by pain. The artist suffered from rheumatoid arthritis that gradually incapacitated him from exercising his trade. However, through tenacity worthy of mention, Renoir invented devices of all sorts to continue to paint, ranging from easels with pulleys to paintbrushes tied to his deformed fingers. Painting for him was both a physical necessity enabling him to stay active and feel useful; as well as a mental and emotional need, to evade his problems and transmute pain through art.

Currently, institutions like the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, are already in discussions about the relationship between chronic pain and overexposure to an activity, and how the latter can be highly debilitating and affect the health and daily life of the afflicted.

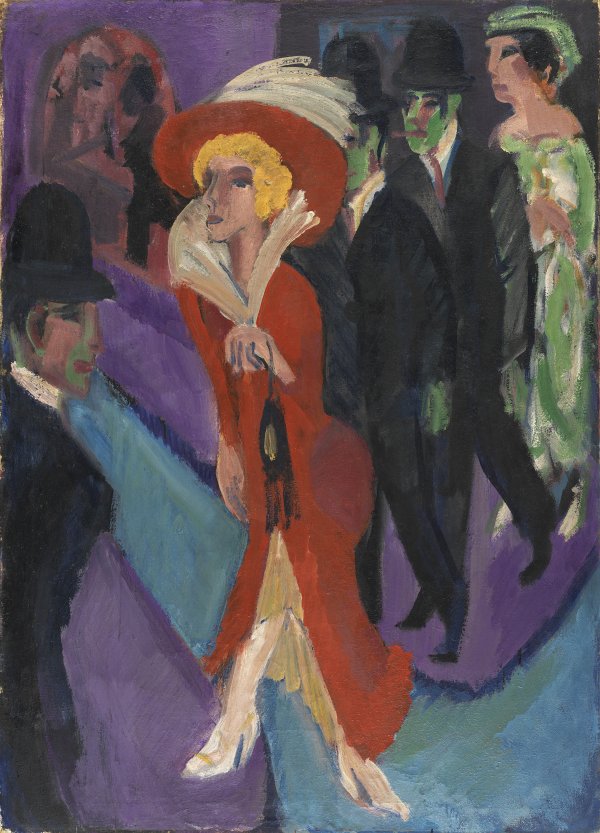

Street with Red Streetwalker

Pain and trauma.

The artist’s own pain.

Factors related to pain: context/environment.

For the length of World War I, Kirchner, the founder and driving force behind the expressionist group, Die Brücke, faced one of the most trying periods of his life. The context of the war, the dehumanization of city life, the hostile and asphyxiating climate and the humiliation and degradation imposed by the victors all left their mark on his art.

The war was a deciding factor in shifting visual languages and the advancement of avant-garde propositions. A new style was needed to narrate a conflict as distinct as the one that was unfolding, a global-scale war, with death and injury statistics never seen before along with a level of destruction and devastation never previously experienced. Imagery would become one of the best vehicles for expression.

Kirchner was mobilized as a soldier, which led to sharp physical and mental decline. He endured his brief stint in the army as an unbearable situation that plunged him into profound states of depression. The war, which he called, “the carnival of death,” was for him not only an oppressive experience but also sterile from an artistic perspective. In 1915 he was disqualified from the army and moved to Davos, where he was isolated for the remainder of his life. The nervous breakdowns he suffered caused him to be committed to various sanatoriums until the year 1917.

His paintings from 1915 are the most representative of this period of personal crisis and psychological depression. There we encounter a somber and disturbing approach to subject matter. Bodily figures piled into claustrophobic spaces, angular characters with violent attitudes and gestures, an atmosphere of unmistakable repression.

Works such as Street with Red Streetwalker, explore themes like desolation or in-communication, not so much as philosophical reflections, but rather as lived personal experiences. Painted in Berlin in 1914, it reflects Kirchner’s fascination with large metropolises. The artist painted numerous street scenes highlighting the dehumanization of life in such spaces. Artists like Otto Dix, Alfred Döblin in Berlin Alexanderplatz, or even authors like Dickens and Wilde, already warned about industrial cities as alienating spaces in which the individual would end up dissolved among the masses.

Cities are defined as claustrophobic spaces, with strange, dark streets, disturbing lights, stress-ridden bodies, pain, and disease. Marginalized characters wander aimlessly through them. The composition is properly structured, but at the same time, the angular and deformed style generates, via the use of diagonal planes, a space that is unstable and asphyxiating. The arbitrary use of color or thick brushstrokes intensify this sensation. Visual elements serve to convey specific sensations tied to the painter’s state of mind.

The central character, clad in striking red, appears at a street intersection; alone but transformed into the center of attention of mens’ gaze; a symbol of bourgeois society’s double standard. The scene is imbued with tension that seems to presage the events that are about to unfold. Everyone looks at her, but nobody is conscious of her actual circumstances; they are completely unable to comprehend her pain.

Following the arrival of the Nazis in Germany, Kirchner, along with other colleagues like Klee, Kokoscha or Kandinsky; was labelled a degenerate artist. His paintings were showcased at the famous exhibition of 1937, as an example of an abomination and attack against German culture. His work was ridiculed, sold at a loss or –even– destroyed. Suffering accompanied Kirchner right up through his final days.

Composition in Colours / Composition No. I with Red and Blue

Pain and trauma.

The artist’s own pain.

Invisible and silenced pain: the denial of pain.

In 1917, he was starting to get his collective artistic project, De Stijl (also known as Neoplasticism), off the ground; it was a group with a shared vocation to create that brought together artists like Van Doesburg, Mondrian, and Van der Leck .

Within a context marked by polarization, pain, and confrontation; they aspired to use art to build a new world order that sought perfection, tranquility, and balance.

Inspired by classical proportions and canons, and by an association equating mathematics and geometry with order and beauty; they reduced to a bare minimum the basic elements of the image, by using lineal and geometric shapes and primary colors that made the piece simpler and more straightforward to contemplate and were familiar to all viewers.

They did not wish to depict anything identifiable from reality; the figurative style entailed, for them, a reference that disrupted the pure relationship with a work of art.

The value of the piece resides in the painting itself as a set of lines, shapes and colors that helped the viewer to experience different sensations.

But Neoplasticism was not an open collective nor was it receptive to other ideas or values; theirs was a visual and esthetic language that aspired to be universal but failed to include everyone. The basis for their equilibrium was instability; a dialogue between contrary perspectives: vertical-horizontal, light-dark, large-small. Neither was it an organic, living art form since they avoided real features like pain. Their apparent tranquility conceals tremendous tension and a need for their own order through ataraxia, a psychological mechanism for self-control and concentration that facilitates reaching an objective; but once achieved, it demands the emotional expression of everything that had been felt.

Tranquility and balance stem mainly from geometric abstraction; more of a desire for change than reality itself. In a world littered with conflicts, instability, changing structures and reference points and a sense of alienation and distancing from the group, pain and suffering existed and were endured by all.

Mondrian strives through his painting to transcend the physical, intellectual, and emotional; at a time when it was hard to get away from chaos, war, anguish, and suffering. Several years after completing this piece, he took exile in the US after a stint in Paris and Berlin while fleeing from the Nazis. In America, surrounded by skyscrapers, jazz and new vitality, his style would shed its earlier stiffness. His painting would thus serve a new period and purpose.

Pain and suffering are both individual and collective, but we are not prepared for them, since we are taught to silence, conceal or deny them. Many emotional issues that are not visible are difficult to notice or treat. Without healthy and open exposure to pain, the latter can deeply affect the afflicted and their environment.

Emotions provide us with valid experiences for confronting other moments or episodes in life; they are part of a learning curve; they are resources to be used on the road to our own recovery. Pain is also necessary for survival and plays a protective role: its purpose is to cause the reflex reactions that keep us from hurting ourselves; both for the afflicted as well as their close relations. Following a traumatic event or the experience of silenced chronic pain; emotional intelligence and healthy relations are key; and especially, communicating the traumatic experience and getting professional help in our immediate environment are of the utmost importance.

Portrait of a Man (Baron H.H. Thyssen-Bornemisza)

Art and improving quality of life.

Pain, a feeling shared by all.

Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s passion for art was a sentiment inherited from his grandfather and his father. He placed all his determination and effort into maintaining the family collection and helping it to grow, and put together one of the most important private collections in Western Europe and the world.

He considered art to have “social significance;” every artwork belonged to “world heritage” and the acquisition of new pieces was aimed not at private possession or viewing, but rather at allowing such art to be “admired by all;” which led him to transform part of that collection into a public museum.

Every painting concealed a story. The qualitative, artistic, and emotional value was essential for him; also, what given pieces of art signified; the adventures undertaken to acquire them; what he experienced while contemplating the pieces. His penchant for acquiring works of degenerate art, does an excellent job of exemplifying the healing, reinvigorating and restorative capacity of art collecting. As Elbert Hubbard once said, “Art is not a thing, it’s a path;” it provides food for thought, intellectual activity, pleasure, peace of mind, and hence, quality of life.

The neurobiologist, Semir Zeki, the creator of neuroesthetics, writes in his Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain, that contemplating a work of art can stimulate blood-flow to the part of the brain connected with pleasure, much like a physical-chemical reaction causes a person to fall in love. The contemplation of art triggers a neurobiological response that can influence our state of mind, our emotions, and our feelings.

The World Health Organization (WHO) published in 2019 a report that discussed “the potential value of the arts, which contribute to crucial core health factors (…), by helping to prevent the appearance of mental illnesses and age-related physical decline; support the treatment or handling of mental illnesses, non-contagious and neurological diseases and disorders; and help with acute, end-of-life care.”

Art is not only soothing for artists and creators but also for those who partake of it through collecting and cultural activities. Esthetic contemplation and contact with Beauty continue to be a means to positively affect processes associated with pain.

When Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza managed to get Lucien Freud to paint his portrait, the artist was already considered as the greatest exponent of the School of London. Following long, innumerable sittings, both painter and collector built a tight-knit and lasting relationship, which led them to share artistic tastes and discuss art.

Before us appears the image of a mature man, whose skin reflects the passage of time as well as his lived experiences. Freud, a painter fascinated by the “invisible powers” that sculpt the flesh o bodies as they change with time; decides to paint a 60-year-old man in his fullness; to capture his essence, not only his appearance.

Given that collecting and love of art define him, behind the Baron, appears the painting by Antoine Watteau, Pierrot Content, part of the collection since 1977 and a reproduction of which Freud hung on a wall of his studio.

In a completely hedonistic society that demands beauty and perfection, the portrait of a 60-year-old man also serves as a mirror in which to contemplate ourselves: how bodies change, how to face the passing of time and what this entails, including sickness and pain; but also, how to enjoy life and its pleasures.

Life expectancy has increased considerably over recent decades, mostly thanks to medical advances. Tackling changes in the body from a conscious and proactive perspective removed from notions of pain and death, influences our individual and collective relationship with a notion common to all: growing old as best we can. Art can help us to become aware and reflect on this process.

In 1994, barely a year after selling his collection to the Spanish state, Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza had to be operated on due to heart issues. Several months thereafter he suffered a serious stroke from which he did not totally recover. He lost his ability to move one arm and was partially incapacitated –requiring a wheelchair to get around– and he had to restrict his public appearances. His emotional state was affected by a family lawsuit that ended with an agreement shortly before his death. He died on April 26th, 2002, and was buried in the family pantheon at Landsberg castle, a site at which his grandfather, August Thyssen, sowed the seeds for what was to become the collection.

His passion for art not only played a relevant role in his coexistence with his illness and the vicissitudes of his life, but also, thanks to his legacy today, the artwork at the Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza helps to improve others’ quality of life as well, from the contemplation of art and the esthetic pleasure this produces to facilitating a reflection on current themes like our relationship to pain.