The path of the Waters. Art and well-being

By Elisa Sopeña

Lord, rip me out of the ground! Give me ears that can understand the waters! Give me a voice that, through love, can tear the enchanted waves’ secret from them.

-Federico García Lorca-

Seas, lakes, springs, streams and rivers inundate the galleries of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, beckoning us to enjoy a pleasant immersion that harmoniously links together art, history and nature. Viewing the masterpieces that comprise the Water Route enables us to disconnect from everyday reality in order to find ourselves via the beauty of water and painting. This route reveals that just like some waters, artistic expression can act as a force to heal our spirit.

The element of water, in its different forms, has inspired some of the most beautiful compositions by the great masters, who have used it as a vehicle to convey their artistic virtuosity, drawing on its important symbolic weight. Sometimes associated with the life cycle, other times with hedonism or regeneration, water and its multiple connotations are found consistently throughout art history as a whole.

Starts on the second floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Portable Triptych with a central Crucifixion

The symbolism of water as a source of life and an element of purification became prominent in the Judeo-Christian world. Since its appearance in the Book of Genesis in the form of the Four Rivers of Eden, the Pishon, the Gihon, the Tigris and the Euphrates, water has been associated with the very beginning of human existence. The liquid element is often mentioned in Biblical stories, bringing secondary meanings that enrich the holy message. Its rich symbolism helps us to intuitively grasp profound, complex contents.

With diverse connotations, water is presented as an essential component in the stories of Abraham, Noah, Moses and Christ’s encounter with the Good Samaritan. One example of this can be seen in the work in the collection, The Pool at Bethesda painted by Giovanni Panini in around 1724, in which this element is associated with healing.

The representation of the baptism of Christ, which has been found in Christian iconography since its beginnings, is one of the four scenes included in the right wing of the Portable Triptych with a central Crucifixion by Lorenzo Veneziano. With his characteristic style that introduces elements from the Gothic world but with a greater naturalistic sensibility and decorative taste, the artist seeks to suggest the real physical presence of God to the faithful by depicting the moment when Jesus was immersed in the River Jordan for purification. The symbolism of the baptism was explained by Saint John Chrysostom: ‘it represents death and burial, life and resurrection as when we plunge our head into water as into a tomb, the old man is immersed, wholly buried. When we come out of the water, the new man appears at that moment.’ The idea of spiritual rebirth is profoundly tied to the baptismal liturgy, through either immersion or infusion, and water, the ambivalent symbol of life and death, is the means that allows that regeneration.

Lorenzo Veneziano chose to represent the moment when Saint John the Baptist places his hand on Christ’s head to administer the sacrament. The impositio manuum takes place in an arid, rocky setting that the water of the Jordan seems to bring back to life. Still nude, without the perizonium or loincloth which became common in these representations at the end of that century, Jesus is blessing the water as two kneeling angels watch him. The presence of the gilded background accentuates the holiness of the work and the introduction of small landscape features in the representation reveal this painter’s naturalistic tendencies.

The Argonauts Leaving Colchis

Mythological waters have been used as the setting of some of the most fascinating epics from classical antiquity. Their depths are inhabited by fantastical aquatic creatures like gods, sirens, nereids, monsters and tritons ready to help or hinder the missions - depending on the occasion - of those brave souls who dare to sail through their domains.

The revival of classical iconography sparked by the Renaissance led to the creation of artworks that illustrated these grand mythical episodes. The thrilling adventure by Jason and the argonauts recounted in book VII of Ovid’s Metamorphoses is the episode that the artist from Ferrara Ercole de’ Roberti chose as the inspiration for this work.

In the fifteenth century, Jason’s popularity had reached its peak after Philip the Good chose the Greek hero as the patron of the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1430. The scene depicted in the panel at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza shows Medea enamoured and fleeing from her homeland with Jason, the hero who had helped her secure the Golden Fleece. They are both embarked on the Argos with the rest of the crew and are getting ready to leave Colchis (currently Georgia) to sail to Iolcos (Greece) through the waters of the Black Sea brimming with dangers and surprises. To highlight the fantastical tone of the story, Ercole de’ Roberti chose to represent the water as a dense mass that is barely distinguishable from the sky.

The story of the argonauts is one of the voyages recounted by classical authors in which the main characters are plunged into missions whose success seems impossible. Faced with all kinds of tests, the waters, sometimes still and tame and other times turbulent and dangerous, become a symbol of a life course which must be travelled to achieve the sought-after objective.

This small panel was part of the front of a wedding cassone. Some of these chests, which were used to store the gifts that the bride received when she got married, were decorated by the great artists of the period. On the left side of the panel, you can still see a fragment of one of the columns with a composite capital which the painter used to distinguish the different scenes depicted on the front of the chest.

The Nymph at the Fountain

‘I, The nymph of the sacred fountain, am resting, do not disturb my sleep’. This is what the Latin hexameter says which shows Castalia, the beautiful naiad depicted in the work by the sixteenth-century German Artist Lucas Cranach the Elder.

In classical mythology, naiads were minor goddesses who kept watch over freshwater. According to the historian Mircea Eliade, these nymphs primarily watched over the running water, springs, fountains, streams and waterfalls where they lived, which they protected with their power. They were deities who drew from the forces of nature and exerted control over them. Quite frequently associated with the ideas of fertility and birth common to water, which are identified by the majority of cultures as female principles, the maternal nymphs raised many of the great heroes of classical mythology since their childhood.

The beautiful Castalia, a companion of the goddess Artemis, tended to meet with the Muses and other nymphs at the fountain at Delphi to sing and dance. The most common version of the myth says that one of those times, Apollo, the god of the arts, fell in love with her. The young nymph, fleeing from Apollo’s designs, plunged into the waters of a fountain, which was then named after her. Κασταλία Fountain, which Herodotus located ‘at the base of Hiampea cliff’ in Mount Parnassus, thus became one of the most important holy sites in Greece. The pythia of Delphi drank water from this spring before entering her trance and offering her predictions, and philosophers and poets went there to seek inspiration, illumination and the gift of creativity. These waters, watched over by a serpent who was the daughter of the god Ares, were considered the source of knowledge and inspiration, as well as a place of purification.

In this work by Cranach the Elder, the water springs up from rocks to form a peaceful lagoon with undulating banks. In this serene landscape, the naiad is reclining on the fresh grass while partridges, which may represent lust, are pecking around her. In the leafy landscape in the background, we can also glimpse four deer, suggesting the enigma and magic surrounding all of nature’s beings.

Landscape with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Born on the banks of the meuse, one of the most beautiful rivers in northern Europe, the sixteenth-century Flemish painter Joachim Patinir is considered the most prominent forerunner of landscape as a genre in itself.

The artist was a pioneer in expressing emotion and sentiment via representations of nature, and water played an important aesthetic and prime symbolic role in his works.

This horizontal panel adapts to the scheme the painter commonly used in his works, in which the true focal point is nature, while the small figures invert the traditional hierarchy to become secondary elements within the composition, subordinated to the predominance of the landscape.

The themes of his oil paintings are primarily religious, and they are always set in magnificent natural settings full of astonishing rocky outcroppings, leafy groves and greenish-bluish waters. His favourite episodes include several in which rivers, streams, springs, ponds or lagoons play an essential role in the story; examples include the baptism of Christ, the crossing of the River Styx and the rest on the flight to Egypt, the subject of this work.

The scene showing the Holy Family resting is set in a landscape with a river wending its way through it and a small spring from which cool, crystalline water bubbles up. Both elements have various profound symbolic meanings in the biblical texts. The Holy Scriptures begin and end with allusions to flowing water: the four rivers of Eden in Genesis and the river springing from Christ’s throne in the Book of Revelation. Springs, wells, streams and seas all play an essential role in the Bible as symbolic places. Living Waters are a sign of blessing, as expressed by Jesus’ words in the New Testament when he speaks to the Samaritan woman: ‘Whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life.’

Pastoral Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

The biblical passage of the flight to Egypt also served as inspiration for the work of another great landscape artist: Claude Lorraine, whose works managed to convey an idyllic harmony between human beings and nature. Through his representations of luminous amber skies, impressive tree stands, transparent waters and ancient ruins, the French painter’s works evoked an image of plenitude befitting a mythical Arcadia in which order and beauty prevail.

This view belongs to the master’s mature period and was painted in a vertical format, which is somewhat unusual in his oeuvre. From a high vantage point, Lorraine introduces us into this landscape in which the zigzagging river forms the backbone of the composition and becomes a crucial symbolic motif. Claude Lorraine depicts the river with extraordinary virtuosity in this work. Through small, light brushstrokes, the painter masterfully recreates the glimmers on the surfaces and the different tones that the water has at different points along its course.

The emblem of all journeys, including our existential journey, the image of the river effectively conveys the idea of the movement of water as a metaphor for the passage of life. This incessantly running element in constant transformation is also associated with the irreversible passage of time and ceaseless change. We can find similar symbolism in the literature of Jorge Manrique (c. 1440- 1479) when the Castilian writer compares lives with rivers leading to the sea. In Lorraine’s landscape, the running water also conducts our eyes to the ocean at the end of its journey.

Neptune and Amphitrite

The four years that the painter Sebastiano Ricci spent in Rome in the 1690s led mythical themes to figure more prominently in his works. The goddesses of antiquity came to feature in several compositions he made during this period, in which he used a style characterised by vivid colours and striking plays of shading.

In this painting, the artist from Belluno draws us into the celebration of the wedding of Neptune, the god of the sea, with the beautiful nereid Amphitrite. This work, which was acquired for the Thyssen collection in 1982, forms a pair with a canvas celebrating another wedding, that one between the god Bacchus and Ariadne, daughter of King Minos of Crete.

Neptune (Poseidon in Greek mythology) was the god of water, the brother of Jupiter and Pluto, and was feared for his power to control earthquakes. Cronos awarded him total dominion over the wet element, and just like the ocean where he reigned, he was attributed with an unpredictable, mysterious, savage and at times malevolent character. Traditionally represented as a mature, bearded man with a muscular build, his attributes are the trident and the crown, with which he is depicted in this work.

A wedding cortege made up of a triton, sea nymphs, erotes referring to the wedding and fantastical aquatic animals accompany the god as he celebrates his wedding with Amphitrite, whom Homer called: ‘the blue-eyed one’. The beautiful girl is a nereid, one of the 50 daughters of Nereus whom Neptune fell in love with as she was dancing with her sisters in Naxos. Even though the young woman initially rejected the marriage proposal from the god of the sea, she ended up assenting and becoming his wife. She symbolises the more pleasant aspects of the sea: She calms the fury of the waves and represents the opposite temperament of her husband.

In the Modern Age, when this work was made, water became extremely important in the urban development of the West. Accordingly, the motif of Neptune and Amphitrite became common in many of the fountains designed then. The symbols of water par excellence, the monumental fountains developed to these gods, representing them either together in harmony or each independently, filled the squares and palatial gardens of the leading European cities.

The Foot-Bridge

In the eighteenth century, numerous treatises were published in France which contributed to the development and rise of the picturesque garden. The ideal of the ‘return to nature’, advocated by the philosopher and naturalist Jean-Jacques Rousseau, viewed rural life as a more authentic alternative of existence that was closer to our origins because of its simplicity and humanity.

This work by Hubert Robert turns this philosophy into a visual reality. The artist represents nature released from the geometric grids that had constrained palatial gardens until then. It brings to fruition a dream of a re-encounter between humans and a natural space that has become free once again.

Named the Dessinateur des Jardins du Roi in 1778, the painter also managed to capture his ideas directly in nature through the designs he made for the gardens of Versailles, where he served as an advisor for Queen Marie Antoinette’s Petit Trianon and Le Hameau. Hubert Robert also created impor- tant decorative ensembles, many of which were meant for spaces that were directly connected to the gardens. Precisely, this work at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza has been associated with the assignments which the master made for some of the private residences of the period, most likely as part of the decor of a room, like a tableau de place.

This work shows how water plays a prominent role in this picturesque nature. Everything in the picture revolves around the river, from the four strollers stopped on the foot-bridge to watch it flow to the boy preparing his nets to try to fish in the river, to the painter who has been seduced by its beauty and is taking sketches from life on the riverbank. Water transcends its status as part of nature to become a symbol of union among human beings, as well as between them and their environment.

Stormy Sea with Sailing Vessels

Seventeenth-century dutch painting shows the profound relations between the inhabitants of the Netherlands and the sea via its impressive seascapes. Grateful for all the wealth and commercial and military success that the seas had provided their land, the Dutch were nonetheless keenly aware of the major dangers entailed in sailing it.

Land reclaimed from the sea, kilometres of coasts, countless canals and beautiful rivers shape the Netherlands as a territory where human beings necessarily have to strike a balance in the way they live with their environment and with water. Both a travel route and a source of life and pleasure, water also has immense destructive power. Aware of this ambivalence, the artists from this century used a wide array of representations to express their complex, thrilling association with this element. The scenes of summertime enjoyment on the coasts, ice-skaters enjoying themselves on the frozen waters of the canals and the might of the Dutch fleet contrast with tempestuous seascapes in which the ships and their occupants are struggling against the raging sea.

The symbolic intention associated with this type of representation may also be related to the view of existence as a fraught journey in which human beings, like sailors, have to grapple with all kinds of perils, from which they will emerge victorious or not depending on their choices. From the religious standpoint, these scenes link up with the Christian hope of avoiding a spiritual shipwreck, the way Saint Paul defined the fall into disgrace of those whose souls are not anchored in Christ. In this work by Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael, the presence of maritime signals comprised of stakes showing ships the safe places where they could dock may be related to this idea of salvation, in which God is a safe harbour, man’s last refuge in the storm.

A Stormy Sea

During the enlightenment, painters expressed a keen interest in depicting uncontrollable phenomena and the power of nature, anticipating the fascination that the masters of Romanticism would feel for them. The devastation and visual drama caused by a storm at sea inspired the creation of numerous artworks which convey humans’ insignificance compared to the power of the elements.

The paintings of Claude-Joseph Vernet, the most admired painter in the sub-genre of seascapes in the mid-eighteenth century, take delight in describing these types of storms, which he contrasts with scenes of calm nature. These pairs of paintings, which show the duality of nature, became one of his hallmarks. (see A calm Sea).

Signed and dated by Vernet in 1778, both works are good samples of his style, which reveals the influence of seventeenth-century Dutch painting and traces of the art of Claude Lorraine. Both compositions follow a scheme which is quite common in Vernet’s works: two-thirds of the composition is occupied by the sky, making it a prime feature, while the water, either calm or stormy, tends to be preceded by rocky outcroppings in the foreground, where Vernet situates his figures.

Until the late eighteenth century, when bathing in the sea was first prescribed for therapeutic purposes, it was considered a hostile, dangerous medium for human survival. During this century, there was a steep increase in maritime sailing, which came with an increase in naval tragedies. Reflection on these dramas at sea is at the root of an entire painting tradition in which shipwrecks served as the inspiration for extraordinarily dramatic works with broad visual possibilities. In Stormy Sea, dynamic diagonal brushstrokes create the appearance of torrential rain falling upon the rough sea. Several men are trying to save the crew of a ship that has wrecked against the rocks, the only part of which we can see are the falling masts.

The opposite of this tragedy is an exceedingly beautiful, serene representation of the warm evening light on the placid waters as groups of fisherman toil at their job. Everything is harmonious in this warmly coloured composition, and its keen observation of nature, soft brushstrokes and decorative touch make Vernet one of the most captivating landscape painters of the eighteenth century.

Continues on the first floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

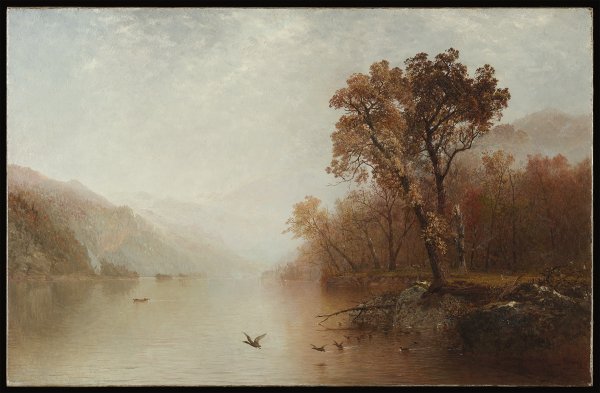

Lake George

The US President Thomas Jefferson wrote in a letter to his daughter Martha in 1791 that the waters of Lake George were the most beautiful he had ever seen, bar none. Indeed, with its crystalline surface surrounded by impressive mountains, Lake George is a wondrous site whose beauty has inspired the works of many US painters.

In addition to its magnificence, what makes Lake George stand out from other popular locales is its prominent place in US history. The site of several military campaigns during the French and Indian War (1754-1756) and the American Revolution (1776), its rich past coupled with its beauty were the perfect combination for expressing the burgeoning national pride through depictions of the lake. Nicknamed the Queen of American Lakes, this expanse of water is the largest in the Adirondacks, and called Lake Horicon, it served as the backdrop of the events recounted in the 1826 James Fenimore Cooper novel The Last of the Mohicans.

Water is a symbol of culture and identity that is inherent in the development of civilisations. People form spiritual and emotional bonds with the rivers, springs, seas or lakes around them. Water is not only an essential element for our survival, but it also represents an image of identity, pride, belonging and rootedness. After its independence in 1776, and especially in the early nineteenth century, US artists became aware of all the possibilities harboured by their land and its waters, and they understood that landscape painting, which they used to showcase their impressive landscape to the world, enabled them to define their nation while representing it.

John Frederick Kensett belonged to the second generation of landscape painters in the Hudson River School, which turned Lake George into one of their favourite motifs. This work is an exquisite example of the mature style of this artist from Cheshire. The luminosity he depicts in the painting enables us to appreciate the iridescent tones of the water and the subtle glimmers it causes on the mountains and plants, conveying to the viewer the atmosphere depicted in a profoundly sensorial way. This glorification of US nature and its representation as a new Eden, a promised land not yet contaminated by civilisation, reveal a pre-ecological view that proved a harbinger of today’s environmental awareness.

The Water Stream, La Brème

Gustave Coubert´s paintings captured his devotion to water, a symbol of the genesis of life. A native of Ornans, the city known as the Venice of Franche-Comté, water is as prominent in his work as it is in the land of his birth. The artist depicted streams, wells, springs, rivers and seas with the fervour of someone who views nature and its elements as fundamental active forces.

Courbet’s fascination with the landscape genre is closely tied to his artistic vision and personality. An independent, transgressive, free-spirited painter, he found nature to be the most authentic source of inspiration. ‘It doesn’t matter where I am’, he said, ‘I’ll always be fine as long as I have nature before my eyes’.

The beauty of La Franche-Comté, with its rocky mountains, dense vegetation and small rivers and waterfalls, was a common motif in his works which he returned to many times throughout his career. This intense bond with his home enables us to interpret his depictions of this landscape as a kind of autobiographical reflection, an extension of his numerous celebrated self-portraits.

The spot depicted in the work at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza is a view of a stream, La Brème, specifically the place where its water burbles up to the surface from an underground stream called Puits Noir. The master constructed two large tree stands that shelter the crystalline water, which he painted with his usual technique conveying the materiality of nature via different textures. His virtuoso use of the spatula and his quick, loose brushstrokes prompted the admiration of other artists of his era, including Paul Cézanne. Given their sensuality, landscapes like this one have been interpreted by some authors as sexual metaphors, associated with other explicitly erotic paintings like The Origin of the Universe (painted around the same date).

One of the most moving aspects of Gustave Courbet’s works is his extraordinary ability to convey the place that inspired the composition. The precision with which the master describes the environment enables us to imagine the rippling of the water amidst the rocks, the rustling of the leaves blown by the wind, the moisture in the air and the coolness of the water. Viewing his works becomes a multisensory experience which enables us to enjoy nature and makes us aware, through emotion, of the need to preserve our natural heritage for future generations.

In a letter dated 1877, doctor Paul Collin, who treated Courbet during his illness, wrote that the artist told him as he was dying: ‘I’m like a fish in water. If I could dissolve in the lake waters, I’d be saved.’ These moving words reveal his profound, eternal bond with water, the element that inspired some of his most beautiful compositions.

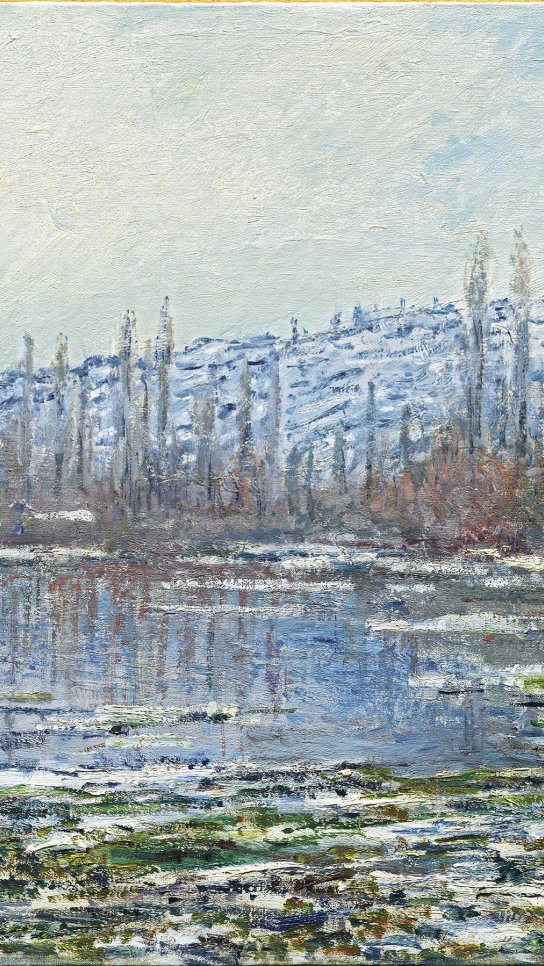

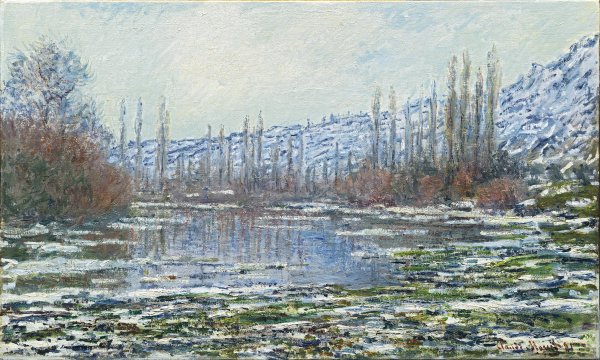

The Thaw at Vétheuil

‘He is one of the few painters who knows ho to paint water without silly transparency, without deceitful reflections. In Monet, the water is alive, deep and above all true.’ The French writer Émile Zola dedicated these words to Claude Monet in 1868.

The new way the impressionist master reflected the qualities of water in his works captivated his contemporaries, who soon noticed the clear prominence of this element in the artist’s paintings.

Monet loved water and painted it his whole life in all its guises, delighting in representing its multiple possibilities. His fascination with this motif reveals his keen interest in capturing in art everything ephemeral and changing in nature. And there are few such sudden and visually spectacular phenomena as a thaw.

December 1879 and January 1880 were extremely cold in Paris and its environs. The heavy snowfall and frozen iciness caused by anomalously extreme temperatures transformed the landscape in this part of France and even froze the Seine River where it passes through Vétheuil, the town where the painter lived. The rise in temperatures after this difficult episode led to an impressive thaw which inspired one of the artist’s most celebrated series.

With the extraordinary insight that led Édouard Manet to be nicknamed the Raphael of Water, monsieur Monet captured all of this element’s variations. Through juxtaposed, loose, quick brushstrokes and the use of a limited palette, he transferred the appearance of snow, ice, water and frost to paint. The virtuosity with which he described the wintry environment reveals why this artist has been considered one of the top representatives of the popular effet de neige in impressionist painting.

The waters from the thaw in Vétheuil speak to us of silence and stillness, convey a kind of elegiac tone and prompt us to think about the artist’s sadness after the tragic loss of his wife Camille the previous autumn. Yet at the same time, the waters of the Seine also seem to symbolise the hope of renewal. Monet depicted this water course his entire career. As he said himself: ‘I’ve painted it my entire life, at all times of day, in Giverny, Rouen, The Havre’.

In Port

During the first World War, the artist Albert Gleizes and his wife, the painter Juliette Roche, lived between New York and Barcelona. In Port is a work in which the master used the cubist language to synthesise and project the importance of these two cities in his life and art.

As the historian Christopher Green has claimed, ‘the port represents the flow of experience through space and time’. And water, which is depicted in this work via synthetic, undulating lines, is the element that makes this flow possible. His constant comings and goings across the ocean from one city to the other allowed Gleizes’ retina to store a vast trove of impressions.Those images are the ones he used superimposed upon each other in a work that not only is an extraordinary argument in favour of cubism but also represents an emotional tribute to these two cities.

The black prow of the transatlantic ship plies the waters that connect views of Barcelona’s port buildings and Santa María del Mar basilica with those of New York’s skyscraper and the braces of one of the most beautiful bridges in the world, the Brooklyn Bridge. The aquatic element symbolises the journey, the union between these places and the peoples who inhabit them. The Gleizes shared experiences on either side of the ocean with artists like Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Robert and Sonia Delaunay and Marie Laurencin and Otto van Watgen. Around that time, they witnessed the birth of dadaism in the United States and enjoyed the summer beauty of the Catalan coast. This entire collage of life experiences, as well as artistic and personal experiences, is projected onto this work, in which water serves as an element of connection that unites two of the most exciting stages in this painter’s biography with rhythm, dynamism, contrasts and fragmentation.

The existence of numerous preparatory studies, such as the four vertical compositions made in New York between 1916 and 1918 and the two early studies of The Port of Barcelona made during his stay in this city, enable us to deduce that Albert Gleizes put a great deal of passion into making this work.

Flower-Shell

The evocative power of shells harks back to the waters from which they come. Their symbolism is inextricably associated with this element as a source of life and fertility. Aphrodite herself, the goddess of love and beauty, was born in water and transported by the winds on the soft seafoam in a seashell.

The goddess, dwelling in the shell like its pearl, as she was depicted by Sandro Botticelli in the Florentine Renaissance, seems to consecrate the association between water and the mollusc in a combination that has inspired artists for ages.

The capricious shapes of molluscs were used to convey mystical, religious, moral or erotic connotations. Their beauty and symbolic capacity, as a more expressive example of the qualities of water, have made them a source of inspiration for artists. Numerous examples of seashells have been represented in art, and they can take on many meanings, as shown by the varieties that can be seen in Roman mosaics, seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes and the works of modern masters like Matisse, Picasso and Dalí.

During the period when Max Ernst had garnered the most widespread recognition as one of the leading figures in surrealism, seashell and flower hybrids became the subjects of some of his most celebrated compositions. The artist associates two such different elements to create an impossible specimen in which the durability of shells, whose beauty does not vanish, merges with the fleeting life of flowers.

This strange and fascinating composition which sprang from the painter’s fertile imagination comes from his Histoire Naturelle, a work made up of 34 images in which the artist showed his first results using the frottage technique. With this method and its sister, grattage – which we see in this work, Max Ernst sought to find a means of expression for painting which combines chance and the artist’s conscious intervention, the equivalent of literary automatism. The texture caused by scratching the surface of the painting generates suggestive forms which release the creator’s and spectators’ unconscious, thus achieving the objective that the artist defined as ‘intensifying the hallucinatory faculties of the spirit such that visions appear automatically’.

Woman in Bath

A woman bathing, a theme that has often been depicted at different points in art history, was reinterpreted in 1963 by the Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein in a work that provides a wonderful opportunity to reflect on the association between women and water in Western painting.

Women’s intimacy has inspired painters because of its artistic and aesthetic possibilities, and through its representation we can trace the evolution of painting on its way to modernity. From representations of nymphs and goddesses bathing to biblical scenes like Bathsheba in the bath to the toilettes and odalisques of the nineteenth century and the baigneuses created by the twentieth-century masters, painters have frequently drawn from this iconographic motif.

The woman shown in the work at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza could be viewed as the evolution of the figures depicted by Ingres and Delacroix. The contrasting models proposed by these two artists were the subject of profound reflection by artists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially Renoir, Bernard, Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso, who used these images as compositional elements in their novel paintings. In the second half of the twentieth century, at the height of Pop Art, Roy Lichtenstein recreated and updated this imaginary within the new style using his hallmark Ben Day system.

With the stereotyped image of a contemporary beauty, the woman draws us into her moment of pleasure. Unlike previous representations, in which the bathers do not know they are being seen, this Woman in Bath is looking directly at the spectator and smiling as if she were a model in an advertisement or the character in a soap opera from the popular culture of the period. By using, isolating and resizing the visual elements from comics in his work, Lichtenstein manages to give an impression of objectivity which transforms the appearance, replacing the mechanical production of this medium with the painter’s manual labour.

The bath, a time of relaxation, enjoyment and introspection, thus becomes a public act which reflects the archetypal image of happiness conveyed by the mass media. Despite this, we can also spy the connection with the past and trace the importance of classical culture to Roy Lichtenstein, who himself acknowledged that ‘the reference is an important part of the content of my works’.

Continues on the ground floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Scene in the Garden of a Seraglio

In the eighteenth century, all things Oriental sparked a great deal of fascination. Scene in the Garden of a Seraglio specifically is part of a series of 43 scenes from life at the court in Constantinople that Giovanni Antonio Guardi painted between 1741 and 1743 on commission from Marshal Johannes Matthias von der Schulenburg.

This prominent German military officer was one of the most important art patrons and collectors of his day, and he was fascinated by works with Turkish themes, a passion that connected with his past as an infantry commander of Venice, for which he won major victories in its struggle against the Ottoman Empire.

Guardi’s work places us inside an exotic, fantastical harem where the sultan is gazing at his favourite while smoking a large pipe. The entire scene is permeated with striking Orientalism, inspired by the prints made based on the paintings of the Franco-Flemish painter working in Constantinople, Jean-Baptiste van Mour, along with a strong dose of imagination, which can be detected by the Baroque appearance of the location where the action takes place. Despite the inventiveness of the pittore Guardi, one aspect that is very revealing is the importance he attached to representing water in scenes inspired by the Oriental world.

Water is the element that forms the backbone of Islamic culture, as it is extremely important in all aspects of daily life, especially the spiritual realm. Water is holy, and the Quran states that ‘all living beings are made of water’. This circumstance, coupled with its limited presence and the difficulty of obtaining it in certain regions, led water to be highly prized.

In his work The Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun, the famous fourteenth-century Tunisian historian, says that for life in a city to be pleasant, several conditions must be considered when founding it, the first of which is the existence of a river or springs with plenty of pure water within its land, as water, considered a gift from Allah, is an extraordinarily important aspect.

Proof of the significance of this prized element in Muslim culture is the development of hammams, whose basic structure was based on Roman baths. The alternation of different rooms at different temperatures fostered both hygiene and enjoyment, in addition to covering ritual, social and spiritual needs, as they were also places of rest and gathering.

Diana Bathing (The Fountain)

In ancient Greece bathing was an act of purification. Statues of gods and goddesses were the subject of ritual ablution that symbolised regeneration. Water was viewed as a feminine element, the bearer of life and a power that fostered change and renewal, which largely explains the ancients’ veneration of this element.

The figure represented in this work by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot is the goddess Diana, Arte- mis in Greek mythology, the main character in a story that the artist admired a lot and had already depicted in his paintings: the myth of Diana and Actaeon, as told by Ovid in book III of his Metamorphoses. In this episode, the goddess and her nymphs are caught off-guard by the young hunter from Thebes as they are bathing in the wooded pond in the idyllic Gargaphia valley. Enraged by his intrusion, Diana pours waters of vengeance on Actaeon’s head, which turns him into a stag to punish him for his audacity at having gazed upon her nude.

In the work in the Carmen Thyssen Collection, Corot focuses on the moment prior to when Diana discovers that she is being watched, and the story transforms into a poetic evocation. The young goddess is absorbed in her bath, a time of true introspection and connection with nature. Droplets of water splatter the vegetation around her, and we can see the reflection of her legs in the mirror-like crystalline pond. The artist suggests a lyrical universe in which the beauty of the water and the natural setting merge to create the perfect context for viewing the female body.

Known primarily for his contribution to nineteenth-century French landscape painting, Corot was also a great painter of the human figure, even though he made these for his own pleasure and only seldom displayed them at the Paris Salon. Although his early biographers attached less importance to this facet of his oeuvre, the artist easily sold his paintings of figures; proof of this are the receipts and letters still conserved, which reveal his intense activity in this sphere. In one of his letters to his brother Theo, Vincent van Gogh complained that Corot’s paintings of this kind were less known than his landscapes.

To depict the goddess of the hunt, Corot chose Emma Dobigny as his model, a young woman who had previously posed for the artist, whom we can also recognise in works by other contemporary painters like Degas and Puvis de Chavannes. Dobigny was famous for her beauty and vitality, and while other artists rebuked her because she was unable to be still, Corot particularly appreciated her for this aspect of her personality: ‘My purpose is to express life. I need a model who moves,’ said the painter.

Tour resources

The order of the works in this pdf may differ from the recommended order.