By Marta Ruiz del Árbol

The start of the twentieth century ushered in an unprecedented cultural renaissance in the Russian Empire. Artistic life became filled with programmatic exhibitions and impassioned manifestos combining the influence of foreign avant-garde trends with genuine features of Russian culture.

This exceptional occurrence differed from the other art movements that emerged around the time in Europe in one aspect: the participation of women in the so-called Russian avant-garde. Not only were a very large number involved, but they played an extremely active and significant role.

Goncharova, Exter, Delaunay, Popova, Rozanova, Udaltsova and Stepanova were raised and trained in a regime that clung to the values of the pre-industrial era. They nevertheless became pioneers in creating, disseminating and defending the new artistic languages that both fascinated and scandalised Russian (and European) turn-of-the-century society.

Young, intelligent, free and rebellious, they did not form a group, though many of them knew and influenced each other. Their names are associated with the successive movements of the last years of tsarism in Russia (Neo-Primitivism, Cubo-Futurism, Rayonism and Suprematism) and their careers were already established by the time of the successful October Revolution in 1917. With their drive and determination, they not only succeeded in becoming part of the avant-garde on a fully equal footing but in many ways led it, marking an important milestone in art history.

Tour artworks

Natalia Goncharova

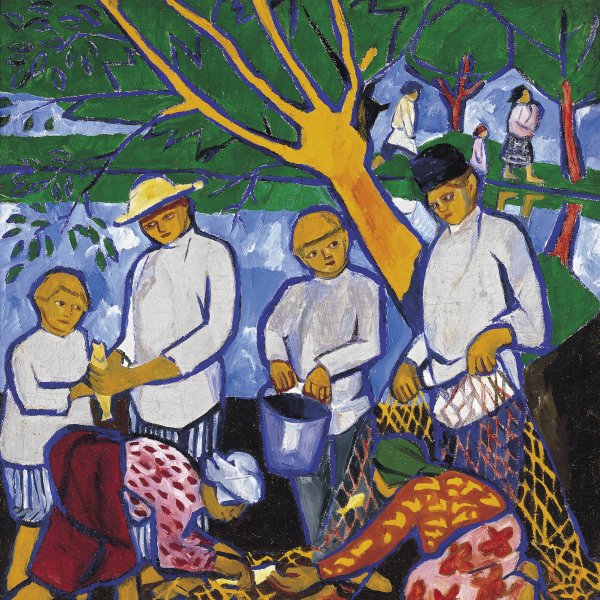

Fishing (fishers)

ROOM H

A pioneer of pioneers

Natalia Goncharova can be considered the first female Russian avant-garde artist and one of the most prominent figures on the pre-First World War art scene in her country. Her solo exhibitions, performances and unconventional lifestyle made her the target of much criticism and fuelled the legend of a wild, indomitable artist.

In her first works of the late 1900s, Goncharova combined an interest in European avant-garde movements with inspiration from Russian folklore and popular arts. Following this initial Neo-Primitivist phase, in which her admiration for Gauguin and Matisse was apparent, she began to explore Cubism and Futurism and later developed Rayonism together with Mikhail Larionov. This movement, based on scientific theories of light, aimed to capture the action and refraction of light rays on objects.

The artist travelled to Paris in 1914 to attend the première of the ballet Coq d’or. Her design for the set was the first of many she produced in conjunction with Larionov for Serge Diaghilev. Although the outbreak of the Great War forced her to go back to Russia, in 1915 a call from the Russian impresario led her and Larionov to join him in Switzerland. She would never return to her country again.

The three pictures in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections allow visitors to trace Natalia Goncharova’s artistic career from her early Neo-Primitivism to her final works of the 1950s, when her painting reflected the influence of Art Informel.

In Fishing, executed in 1909, the artista depicted the peasants of the rural area of Polotnianyi Zavod, near Moscow, where she spent long periods during her youth in the house the family owned there. She expressed her fascination with rural life – traditionally the mainstay of the Russian population – in canvases where she converted these everyday scenes into a sort of popular epic. Stylistically they display the influence of foreign art trends, chiefly Post-Impressionism and Fauvism. However, unlike the French artists, who had turned their attention to non-western cultures in search of a pure artistic expression, Goncharova was interested in her own cultural roots, which became her true source of inspiration. In 1912, she stated in a lecture that ‘Cubism is a positive phenomenon, but it is not altogether a new one. The Scythian stone images, the painted wooden dolls sold at fairs are those same Cubist works.’

Natalia Goncharova

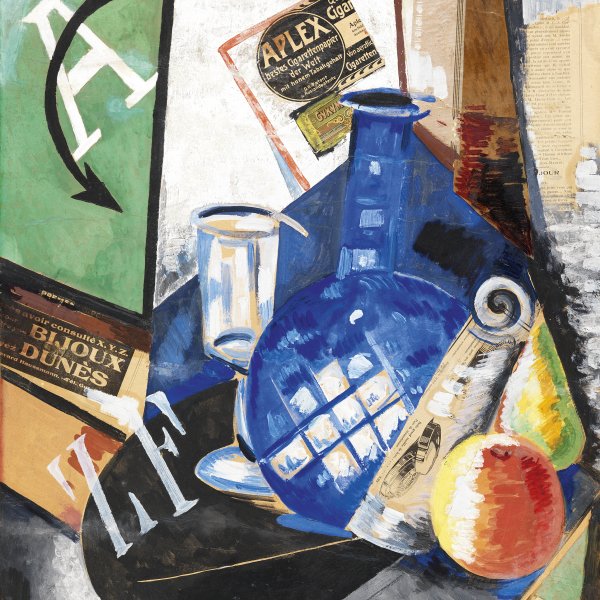

The Forest

ROOM 43

A pioneer of pioneers

Natalia Goncharova can be considered the first female Russian avant-garde artist and one of the most prominent figures on the pre-First World War art scene in her country. Her solo exhibitions, performances and unconventional lifestyle made her the target of much criticism and fuelled the legend of a wild, indomitable artist.

In her first works of the late 1900s, Goncharova combined an interest in European avant-garde movements with inspiration from Russian folklore and popular arts. Following this initial Neo-Primitivist phase, in which her admiration for Gauguin and Matisse was apparent, she began to explore Cubism and Futurism and later developed Rayonism together with Mikhail Larionov. This movement, based on scientific theories of light, aimed to capture the action and refraction of light rays on objects.

The artist travelled to Paris in 1914 to attend the première of the ballet Coq d’or. Her design for the set was the first of many she produced in conjunction with Larionov for Serge Diaghilev. Although the outbreak of the Great War forced her to go back to Russia, in 1915 a call from the Russian impresario led her and Larionov to join him in Switzerland. She would never return to her country again.

The three pictures in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections allow visitors to trace Natalia Goncharova’s artistic career from her early Neo-Primitivism to her final works of the 1950s, when her painting reflected the influence of Art Informel.

The Forest, also entitled Rayonist Landscape or Rayonist Perception, was painted by Goncharova in 1913, the year she and Larionov signed the Rayonist Manifesto. The work, which was shown in the Mishen (Target) exhibition during that year and marked the new movement’s presentation in society, represents the light rays that strike the interior of a forest and enable us to perceive the scene. Although it retains references to the real world and the tree trunks and tops are recognisable, the interweaving pattern of coloured rays stretching in different directions gives the picture an abstract appearance.

Natalia Goncharova

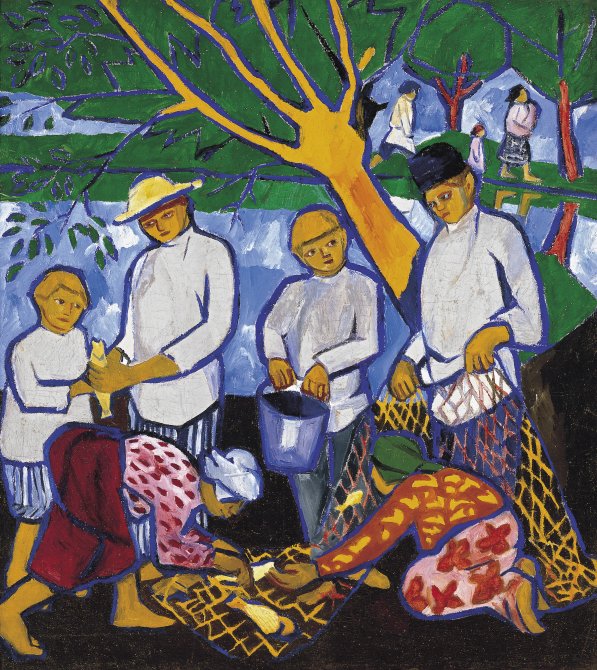

Composition with Blue Rectangle

Not on display

A pioneer of pioneers

Natalia Goncharova can be considered the first female Russian avant-garde artist and one of the most prominent figures on the pre-First World War art scene in her country. Her solo exhibitions, performances and unconventional lifestyle made her the target of much criticism and fuelled the legend of a wild, indomitable artist.

In her first works of the late 1900s, Goncharova combined an interest in European avant-garde movements with inspiration from Russian folklore and popular arts. Following this initial Neo-Primitivist phase, in which her admiration for Gauguin and Matisse was apparent, she began to explore Cubism and Futurism and later developed Rayonism together with Mikhail Larionov. This movement, based on scientific theories of light, aimed to capture the action and refraction of light rays on objects.

The artist travelled to Paris in 1914 to attend the première of the ballet Coq d’or. Her design for the set was the first of many she produced in conjunction with Larionov for Serge Diaghilev. Although the outbreak of the Great War forced her to go back to Russia, in 1915 a call from the Russian impresario led her and Larionov to join him in Switzerland. She would never return to her country again.

The three pictures in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections allow visitors to trace Natalia Goncharova’s artistic career from her early Neo-Primitivism to her final works of the 1950s, when her painting reflected the influence of Art Informel.

Composition with Blue Rectangle, dating from around 1950–59, is a late work produced by Goncharova when she had been living in France for nearly four decades. The artist, who seldom explored the purely non-objective aesthetic and preferred to always include a reference to visible reality, might be making an allusion in this small study to the famous launch of the first Sputnik in 1957 and to the series of cosmic pictures she painted on the subject.

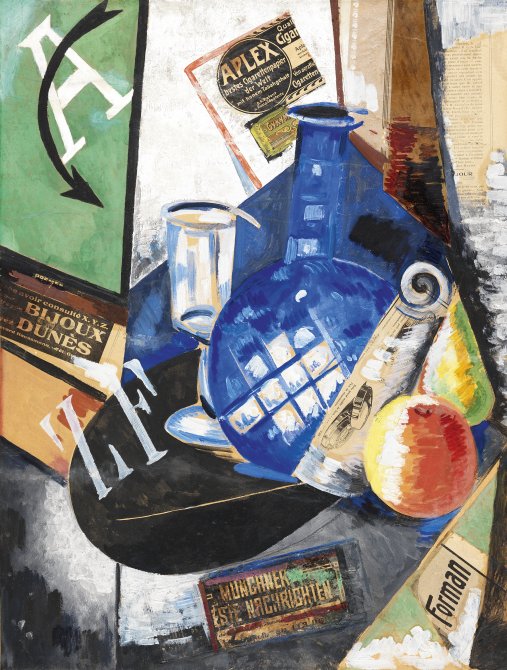

Alexandra Exter

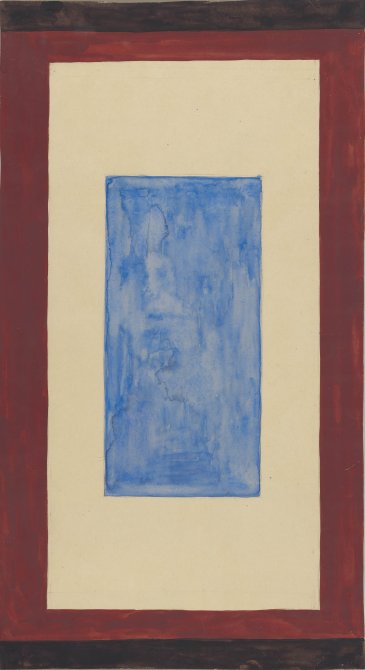

Still Life

ROOM 43

The first traveller

Alexandra Exter was a key figure in the connections between the Russian avant-garde and art trends then emerging in western Europe. Beginning in 1907, her early interest in the Parisian scene led her to spend long periods in the French capital, where she met Pablo Picasso and George Braque, among others. Fascinated by the possibilities of the new Cubist language, she immediately adopted it and became one of its leading advocates in Russia.

Unlike her western counterparts, however, she decided not to shun colour, which she regarded as the be all and end all of painting. This concern was also linked to the importance the Russian avant-garde artists attached to their own cultural traditions – in Exter’s case Ukrainian. Her contact with the Delaunays and the Italian Futurists spurred her to develop an interest in the introduction of movement and further strengthened her commitment to colour.

When the Great War broke out, Exter returned to her country. She was attracted to the work of Kazimir Malevich and produced her first non-figurative paintings under his influence. During these years she began collaborating on theatre productions and in 1921 she became a fashion designer. In 1924 she emigrated to Paris, where she lived for the rest of her life.

Exter probably painted Still Life in Paris, the city where she lived from 1912 to 1914. Her close relationship with the founders of the Cubist movement is clearly visible in this canvas in the fragmentation of the space, the use of collage and even the choice of component objects. However, as stated earlier, the Ukrainian-born painter origin did not espouse Analytical Cubism’s reduced palette, and the vivid colours of this still life attest to the importance of the traditions of her native country in her conception of art.

Olga Rozanova

Man on the Street (Analysis of Volumes)

ROOM 43

The poet-painter

Olga Rozanova is held to be one of the most original women artists of the Russian avant-garde. Despite dying very young, she was a prominent figure on the art scene on account of her firm commitment to non-figurative art and her constant pursuit of new forms of expression.

Rozanova’s beginnings were linked to Futurism, to which she was introduced by the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh, the inventor of the experimental language zaum. She not only collaborated on the design of many Futurist publications but began writing her own transrational poems. In parallel with these activities, Rozanova also painted her first Cubo-Futurist Works in which colour was her chief concern. They were so innovative that Filippo Marinetti decided to include them in the First International Futurist Exhibition held in Rome in 1914.

In 1915 she embraced Kazimir Malevich’s abstract art and contributed to the magazine Supremus, though no issues were published. However, she very son created her own version of Suprematism and coined the concept of tsvetopis, which advocated the absolute power of colour. The works she produced before her unexpected death are the most radically abstract and seem to anticipate American Colour Field painting of the 1950s and 1960s.

Man on the Street (Analysis of Volumes) was one of the pieces Marinetti chose for the Futurist Exhibition in Rome in 1914. In fact, the Italian poet kept it until he died. In it Rozanova, who never left Russia, gives a brilliant interpretation of the new art trends that were arriving from Italy and France. It combines the fragmentation of Cubist space with an interest – in tune with Futurist concerns – in depicting the modern city and technological progress.

Nadeshda Udaltsova

Cubism

ROOM 43

The Russian Cubist

Nadezhda Udaltsova’s links to Cubism date back to November 1912, when she travelled to Paris with her friend Liubov Popova. Together they attended classes taught by Jean Metzinger and Henri Le Fauconnier at the Académie de La Palette and from this point onwards the Cubist language became the basis for constructing her works. Even years later, when she joined the Supremus group and advocated non-objective art as the culmination of the path to new painting, her works continued to be more closely connected to Cubist art than to Suprematism strictly speaking.

Following the October 1917 Revolution, Udaltsova played an active role in various cultural initiatives and taught classes. She was also a member of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk), though she left it in 1921 over a disagreement with the Constructivist artists, who were calling for abandoning painting as an artistic practice. After returning to figuration in the early 1920s, with a style that embraced to her Cubist origins, Udaltsova gradually progressed towards a more descriptive art in which she reflected her trips to the Urals and Armenia.

Cubism displays the main features of Udaltsova’s mature art. Executed in 1914, two years after her stint in Paris, it is a magnificent example of the mark her time at the Académie left on her. With its programmatic title, it is an experiment in the Cubist fragmented approach. The planes and lines of force create a space from which references to visible reality have disappeared and which coexists alongside signs borrowed from the Analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque.

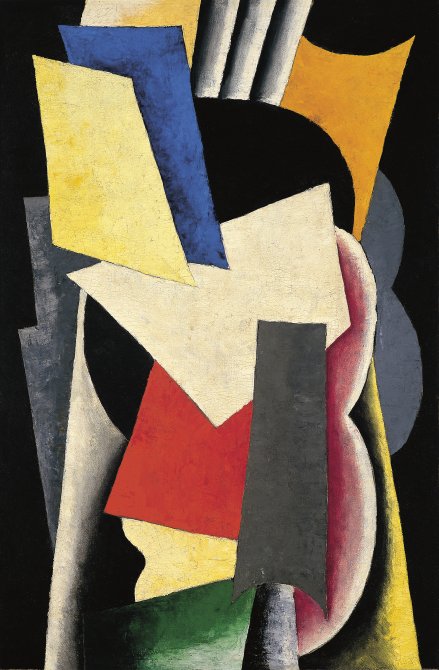

Liubov Popova

Painterly Architectonic (Still Life: Instruments)

ROOM 43

The artist-constructor

Liubov Popova was one of the most prominent Russian avant-garde figures. Referred to as the ‘artist-constructor’ in the exhibition organised after her unexpected death in 1924, she was always notable for her interest in the constructional and structural elements of painting.

From a very young age Popova combined an interest in early Russian art with the influence of what she saw during her many family trips around Europe. Classical Italian art, especially the compositional foundations of the Renaissance style, left an indelible mark on her. She was also attracted to contemporary art trends and in 1912 she and her friend Udaltsova travelled to Paris, where she came into contact with Cubism. A subsequent stay in Italy allowed her to gain first-hand knowledge of Futurism, and she combined both languages in her works.

Around 1916, she produced her first fully abstract works and went on to take part in debates on the validity of the non-objective language and the concepts of construction and composition. During those years her style fluctuated between Suprematism and Constructivism, though she always retained her artistic independence. In 1921, along with other artists of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk), she gave up easel painting and embarked on an important career as a graphic, textile and theatre set designer.

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection features three examples of Liubov Popova’s Pictorial Architectonics, a series executed between 1915 and 1918 in which the artist explored the possibilities of non-objective language.

Pictorial Architectonic (Still Life: Instruments) is one of the earliest examples from this group of paintings and retains certain recognisable references to the Cubist world of objects, such as the outline of the guitar, though geometrisation and overlapping planes are predominant.

Liubov Popova

Painterly Architectonic

ROOM 43

The artist-constructor

Liubov Popova was one of the most prominent Russian avant-garde figures. Referred to as the ‘artist-constructor’ in the exhibition organised after her unexpected death in 1924, she was always notable for her interest in the constructional and structural elements of painting.

From a very young age Popova combined an interest in early Russian art with the influence of what she saw during her many family trips around Europe. Classical Italian art, especially the compositional foundations of the Renaissance style, left an indelible mark on her. She was also attracted to contemporary art trends and in 1912 she and her friend Udaltsova travelled to Paris, where she came into contact with Cubism. A subsequent stay in Italy allowed her to gain first-hand knowledge of Futurism, and she combined both languages in her works.

Around 1916, she produced her first fully abstract works and went on to take part in debates on the validity of the non-objective language and the concepts of construction and composition. During those years her style fluctuated between Suprematism and Constructivism, though she always retained her artistic independence. In 1921, along with other artists of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk), she gave up easel painting and embarked on an important career as a graphic, textile and theatre set designer.

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection features three examples of Liubov Popova’s Pictorial Architectonics, a series executed between 1915 and 1918 in which the artist explored the possibilities of non-objective language.

The other two Pictorial Architectonics, dated 1918 and smaller in size, are fully abstract. These constructions provided the artist with an ideal compositional structure for her paintings that was in tune with Malevich’s Suprematist ideas. However, through the interaction of the various colour planes, Popova imbued her paintings with a dynamism more in keeping with Tatlin’s proto-Constructivism, resulting in works that were highly personal and original.

Liubov Popova

Painterly Architectonic

ROOM 43

The artist-constructor

Liubov Popova was one of the most prominent Russian avant-garde figures. Referred to as the ‘artist-constructor’ in the exhibition organised after her unexpected death in 1924, she was always notable for her interest in the constructional and structural elements of painting.

From a very young age Popova combined an interest in early Russian art with the influence of what she saw during her many family trips around Europe. Classical Italian art, especially the compositional foundations of the Renaissance style, left an indelible mark on her. She was also attracted to contemporary art trends and in 1912 she and her friend Udaltsova travelled to Paris, where she came into contact with Cubism. A subsequent stay in Italy allowed her to gain first-hand knowledge of Futurism, and she combined both languages in her works.

Around 1916, she produced her first fully abstract works and went on to take part in debates on the validity of the non-objective language and the concepts of construction and composition. During those years her style fluctuated between Suprematism and Constructivism, though she always retained her artistic independence. In 1921, along with other artists of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (Inkhuk), she gave up easel painting and embarked on an important career as a graphic, textile and theatre set designer.

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection features three examples of Liubov Popova’s Pictorial Architectonics, a series executed between 1915 and 1918 in which the artist explored the possibilities of non-objective language.

The other two Pictorial Architectonics, dated 1918 and smaller in size, are fully abstract. These constructions provided the artist with an ideal compositional structure for her paintings that was in tune with Malevich’s Suprematist ideas. However, through the interaction of the various colour planes, Popova imbued her paintings with a dynamism more in keeping with Tatlin’s proto-Constructivism, resulting in works that were highly personal and original.

Varvara Fedorovna Stepanova

Billiard players

ROOM J

The frenzied artist

The poet Vladimir Mayakovski defined Varvara Stepanova as the ‘frenzied artist’ on account of her tireless pursuit of new artistic ideas. She relentlessly explored all the trends that emerged in Russia, from Symbolism, Neo-Primitivism and Cubo-Futurism to Constructivism and Socialist Realism.

As the youngest of all the women pioneers, she admired the Futurist poets at the start of her career and wrote her first transrational poems in 1917. They became the basis for manuscript books in which, following Rozanova’s example, she combined text and abstract forms. Her enthusiasm for the triumph of the October Revolution led her to fill her works with figures representing the new humans of the socialist era (robotic, efficient and dynamic). Later on, in September 1921, she joined the group of artists who decided to abandon easel painting. Stepanova, the only artist of her day who had trained in the applied arts, brought her ideas to clothing and textile design and the decoration of public spaces and theatres, and became one of the leading practitioners of Constructivism.

Billiard Players belongs to a series called ‘Figures’ in which the artist made the human figure the centrepiece of her explorations from the late 1910s to the early 1920s. Unlike many of her Russian contemporaries, she was not particularly drawn to non-objective painting and portrayed citizens born in the Soviet era as mechanised automats, though emotional states such as agitation or calm are occasionally found in her depictions. This work stands out from her paintings of this period on account of its large format.

Sonia Delaunay

Simultaneous Contrasts

ROOM 42

A Russian woman in Paris

Although Sonia Delaunay spent most of her time in Paris, everything about her life and work seems to be connected with her Russian origins. Her uncompromising defence of colour, commitment to abstraction and interest in applying her artistic ideas to all kinds of everyday objects were very much in line with the aesthetic principles upheld by many of her fellow avant-garde artists in Russia, with whom she was in contact.

Originally from Ukraine, the young Sonia Stern (later Terk) was adopted by her maternal aunt and uncle of St Petersburg when she was a child. In 1904 she left her country forever to study first in Karlsruhe and two years later in Paris. In the French capital she soon became a key figure on the avant-garde scene thanks to Simultanism – an adventure she embarked on with Robert Delaunay, who became her husband in 1910. Together they explored colour contrasts and the dissolution of form through light, which led them to abstraction.

During the Great War she sought refuge in Spain and Portugal. In 1917 the October Revolution cut off her income from property in Russia and she began to sell her textile creations in Madrid, fulfilling a lifelong aim. She continued to experiment in this field in the early 1920s after returning to Paris, where she became an acclaimed fashion and fabric designer.

Simultaneous Contrasts belongs to a suite of works with the same title in which Sonia Delaunay, starting from an analysis of how light is reflected off objects, achieves an abstract purity in which color is both form and content. The contrasts of complementary and clashing colours create a ‘movement’ that becomes the generator of the new space in modern painting.

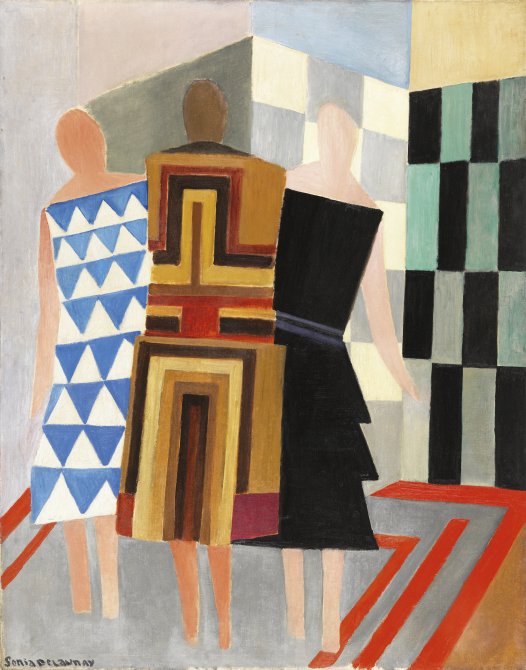

Sonia Delaunay

Simultaneous Dresses (Three Women, Forms, Colours)

ROOM 42

A Russian woman in Paris

Although Sonia Delaunay spent most of her time in Paris, everything about her life and work seems to be connected with her Russian origins. Her uncompromising defence of colour, commitment to abstraction and interest in applying her artistic ideas to all kinds of everyday objects were very much in line with the aesthetic principles upheld by many of her fellow avant-garde artists in Russia, with whom she was in contact.

Originally from Ukraine, the young Sonia Stern (later Terk) was adopted by her maternal aunt and uncle of St Petersburg when she was a child. In 1904 she left her country forever to study first in Karlsruhe and two years later in Paris. In the French capital she soon became a key figure on the avant-garde scene thanks to Simultanism – an adventure she embarked on with Robert Delaunay, who became her husband in 1910. Together they explored colour contrasts and the dissolution of form through light, which led them to abstraction.

During the Great War she sought refuge in Spain and Portugal. In 1917 the October Revolution cut off her income from property in Russia and she began to sell her textile creations in Madrid, fulfilling a lifelong aim. She continued to experiment in this field in the early 1920s after returning to Paris, where she became an acclaimed fashion and fabric designer.

Simultaneous Dresses (Three Women, Forms, Colours) was painted twelve years later, the same year her fashion designs caused a stir at the International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts. Here the artist, who often defended her dedication to the applied arts as ‘a free expansion, a conquest of new space; […] another application of the same research’, transfers to canvas the results of her experimentation with fashion design. The pattern reproduced in the central figure is very similar to her design for a coat for the film actress Gloria Swanson.