By Noelia Romero

A Room of One’s Own invites visitors to explore the galleries housing the museum’s collections and take a closer look at selected works that elicit thoughtful reflection on the role of domesticity in art and the ways of inhabiting a house as a subjectification process from a gender perspective. First of all, we must mention the events to which this tour owes its title: the lectures that Virginia Woolf delivered at Newnham College and Girton College in 1928. Those two lectures grew into the book A Room of One’s Own, the banner of the 20th century women’s rights movement as well as a seminal analysis of the lack of spaces for female cultural production and creation throughout history. Virginia Woolf concluded that the lack of a private life—a room of one’s own, in both the literal and the allegorical sense—is the primary reason why there is barely any hard evidence of intellectual production by women:

At the thought of all those women working year after year and finding it hard to get two thousand pounds together, and as much as they could do to get thirty thousand pounds, we burst out in scorn at the reprehensible poverty of our sex. What had our mothers been doing then that they had no wealth to leave us? Powdering their noses? Looking in at shop windows? Flaunting in the sun at Monte Carlo? There were some photographs on the mantelpiece. Mary’s mother—if that was her picture—may have been a wastrel in her spare time (she had thirteen children by a minister of the church), but if so her gay and dissipated life had left too few traces of its pleasures on her face. She was a homely body; an old lady in a plaid shawl which was fastened by a large cameo [...] Now if she had gone into business; had become a manufacturer of artificial silk or a magnate on the Stock Exchange; if she had left two or three hundred thousand pounds to Fernham, we could have been sitting at our ease tonight and the subject of our talk might have been archaeology, botany, anthropology, physics, the nature of the atom, mathematics, astronomy, relativity, geography.

An emancipating, inclusive framing of the question, “What conditions are necessary for the creation of a work of art?”, this not only underscores the loss and lack associated with the world of women, where tangible works are in such short supply, but also points directly to the need to revise the zones, rooms and spaces conquered or appropriated by man for creative habitation. Workshops, studios, offices, cabins and nature have been, and still are, the containers and content of male artistic creation and merit an exhaustive investigation in their own right. At the same time, they provide a clear benchmark for reflecting their absence in the female universe, so often relegated to the domestic sphere, common areas and family duties. The relevance of those private rooms as paint-worthy motifs often surpasses their testimonial value as spaces of work, artistic and intellectual production, becoming a reflection of the artist’s mindset, a kind of self-portrait.

In one sense, we are what we do, and we leave our mark where we do it. The represented space houses an action or attests to a profession, but it also provides conditions conducive to expressing that subjectivity and places it within a specific framework. However, while male subjectivity is developed, as mentioned, in the workshop, the office, nature or a private interior, female subjectivity transpires in common areas, through the performance of domestic duties and the management of household assets, or in more private, intimate apartments where women are portrayed as muses, embodying male desire. Yet none of these themes display the desires or knowledge of women, nor are they the expression of a productive self. The vast majority of women are therefore depicted as decorative objects serving erotic or family needs. But we do find a few exceptions when they are portrayed by a female artist.

To reflect further on this subject, we will rely on selected works from the museum’s collections of 16th-century Flemish, 17th century Dutch and 18th-century French paintings—with their predilection for interior scenes—as well as works from the dawn of modern art—Romanticism, Impressionism and Symbolism—and the early 20th century, specifically Fauvism and the American realism of the interwar years. All these art movements, and Western art history as a whole, established, recorded and promoted the separation of gender roles, detailing and outlining the possible spheres of action and subjectification assigned to each sex.

We will see all of this illustrated by concrete examples in the galleries.

Tour artworks

Jan de Beer

The Birth of the Virgin

ROOM 10

In this chamber, the Virgin's mother, Saint Anne, is praying after having given birth, consoled by another woman at her side while a third prepares a restorative tonic and the midwife attends to the new-born Mary. The picture, dated to about 1520, portrays an intimate religious scene. The author attempted to humanise the episode and its fgures by creating an ordinary domestic setting for the pathos-charged act of childbirth. Yet the atmosphere has a distinctly aseptic, solemn tone, unnaturally devoid of emotion, although this stylisation is understandable in the context of High Renaissance art. From our present-day perspective, the artist’s decision to depict this passage from the apocryphal Gospel of James is quite interesting. If history, literature and, in general, the vestiges and proofs of our culture have been predominantly crafted by men, what relevance does the act of giving birth have in the history of our civilisation? Are there any instances of such scenes not associated with the religious concept of giving life that predate the 20th century? We have to wonder if childbirth is actually something worth making visible for, as Woolf noted, we cannot measure or assess something that has been omitted from our recorded history. The historical occupations of women, such as care or housekeeping, are those which Woolf says have no benchmark against which to gauge them. “There is no mark on the wall to measure the precise height of women. There are no yard measures, neatly divided into the fractions of an inch, that one can lay against the qualities of a good mother or the devotion of a daughter, or the fidelity of a sister, or the capacity of a housekeeper.” Where there should be marks, there are only absences or holes. The very lack of quantifable standardised criteria to narrate, analyse or dignify those activities is the reason why these visual records in the museum’s collection require a new interpretation.

Maerten van Heemskerck

Portrait of a Lady spinning

ROOM 10

This panel clearly illustrates the aforementioned process of subjectification via a domestic task. The scene, set in a narrow interior utterly devoid of details, focuses on the voluminous forms of the sitter’s garments and the tools necessary for the work she is doing: in the foreground, a spinning wheel and sewing basket, and a pair of shears and a yarnwinder in the back of the room. The girl gazes at us steadily with a satisfied, industrious expression as she holds the thread in one hand and guides it onto the wheel. The spindle and the act of spinning imply her virtuousness and suggest that she lives up to the social expectations of women of her time and status. In addition to symbolising honesty and chastity, the task of spinning is a recurring motif in Dutch art. In some cases the depiction includes a second figure who unsuccessfully tries to tempt the lady and distract her from her duties, thereby praising her imperturbability.

This portrait radiates neatness and modesty thanks to the plain, simple, sober colours of the spinner’s attire, virtues which are further reinforced by the pristine white linen cap that hides her hair. Usually that part of a woman’s body was only revealed in private rooms, with obviously erotic connotations. The dedication and zeal this picture conveys make the act of spinning the true protagonist, and the spinning wheel the main narrative element. In this case, spinning is an activity associated with femininity: it was performed inside the home, not necessarily as a profession but as a skill to be acquired in the process of becoming a woman. It validates the sitter’s gender, reaffirming that clearly defined roles, rather than the moment of birth, corroborate gender identity. As Simone de Beauvoir said, “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.”

For the sake of contrast, we suggest comparing this work with Gerard ter Borch’s Portrait of a Man Reading a Document, which we will see later, where an occupation is represented not only as a defining trait of the sitter but also as paid work, the free exercise of a profession outside the home in exchange for monetary compensation, with the power it brings.

Pietro Longhi

The Tickle

ROOM 16

Pietro Longhi's scene deviates somewhat from our selection criteria, as it does not specifically represent any of the issues related to the male presence or female absence in the private sphere of the home and its multiple modes of occupancy. However, it does offer a novel element in the universe of affect that serves to compare his treatment of the emotional space of private rooms with canvases that we will see later on, such as La Toilette by François Boucher or The Duke of Orléans Showing His Lover by Eugène Delacroix.

Pietro Longhi playfully paid tribute to the erotic game played by two young Venetian aristocrats while a servant looks on. The eyes of the dominant female figure in the picture rest on the viewer, outside the frame, requesting silence with a gesture and a knowing look. She is caressing a sleeping young man with the feather in her right hand, trying to stir him from his lethargy. Meanwhile, a third figure embraces the first and joins in the fun. The female servant, standing apart from this affectionate trio, observes them, emulating the spectator and thus eliminating the voyeur effect we will see in Boucher and Delacroix. She makes us accomplices while simultaneously including us as guests invited to witness the scene. The woman who initiates the game is our protagonist, as she activates the scene.

Here—by now we are in the 18th century—the object of desire is the boy, who enjoys the tickling, and the dominant subject is the young lady, who stares at us and asks us to be discreet. This work, which clearly reflects the bourgeois tastes of the Rococo period, is pertinent to our theme because it also illustrates the separation of traditional gender roles, where women occupied the domain of sensory delights and men that of intellectual pleasures (as we will later see in works like Corner of a Library by Van der Heyden, Portrait of a Man Reading a Document by Ter Borch, or The Reader by Ferdinand Hodler). Rita Segato and other authors believe that the patriarchy arose from the concept of original sin and similar myths, widespread in many cultures, where woman is the embodiment of sin, a slave to her passions, and man is forced to take control, in a triumph of his will and self-discipline, by the cognitive and moral route. Here the woman is inciting another to sin in some way, under the seemingly innocent guise of a tickle.

Jan Jansz. van der Heyden

Corner of a Library

Not on display

This canvas shows a detailed inventory of objects found in a typical study in the early 18th century. It is a room devoted to knowledge and work, where we see a bookcase protected by a heavy curtain and numerous objects related to cartography (atlas, maps and globes), evidence of the interest in discovering the geographical limits of the world and conquering unknown territories that characterised this historical period. We assume that it is a man’s room, as the production of knowledge and all intellectual activity were reserved for men of high social standing. The walking stick leaning against one of the chairs confirms that this space was only used by the man of the house. There are also several oriental elements, like the spear leaning beside the rolled maps and the red silk Chinese tablecloth adorned with floral motifs, which should be understood as a decorative reminder of the conquest of distant lands and the appropriation of exotic materials rather than as a feminising element per se. Finally, the candlestick with the burnt-down candle indicates the hours devoted to study. Although no one is in the room, the narrative quality of the objects allows us to imagine how it was used, the actions that took place there and the guests who were invited to share it: men (possibly the artist himself) of a certain social position with the capacity, power and resources needed to play a part in the production of knowledge. We might say that this room has been appropriated; in Woolf’s words, it is “the offspring of luxury and privacy and space”. It is a room of one’s own, in every sense.

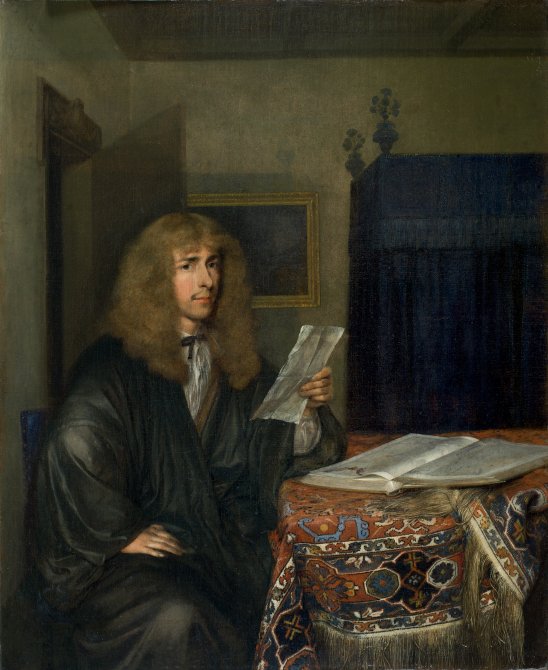

Gerard ter Borch

Portrait of a Man reading a Document

ROOM 27

For most of the History of art prior to the 19th century, when a woman was depicted in the way Gerard ter Borch portrayed this man, she was usually holding something that represented or defined her: a spinning wheel, as we saw earlier, a book of saints, a Bible, a rosary, or a decorative or floral arrangement, among other things. Such elements credited her with moral virtues and honoured her good work, describing her role within the prevailing customs at the time. In the case of this work, the paper in the man’s hands tells us about him, but unlike in female portraits, it indicates that he has an occupation outside the home which gives him financial independence, conferring value upon his individuality without the need to assert his moral dignity. Although the painter sets the scene in a bedroom with the bed in the background—Gerard ter Borch was known for his intimate portraits and domestic scenes—the focus is on the man’s occupation, which in this case gives him a certain status. Once again, Woolf inspired the choice of this picture: the issue was not just the rooms that women were unable to conquer, but also the wages they could not earn and the professions that were not open to them, “because, in the first place, to earn money was impossible for them, and in the second, had it been possible, the law denied them the right to possess what money they earned”.

Pieter Hendricksz. de Hooch

Interior with a Woman sewing and a Child

ROOM 25

Here De Hooch represented a moment in the everyday life of a woman at home, in a common-use room rich in details that doubles as a backdrop. The silent, shy intimacy of this scene is far removed from the ostentatious portraits of wealthy families. It is also a tribute to the work involved in running a household, childrearing, caregiving, domestic chores and the solitude that went with them. Although studies on domestic labour did not appear until after this painting was made, we can say that the prevailing ideology of domesticity considered women to be “natural” caregivers, opening up a resignification of motherhood as something incompatible with so-called “productive” activities. In fact, in the early 20th century, when the custom of receiving a salary in exchange for labour became widespread, domestic work was deemed unproductive. In a way, this picture, like others in the Thyssen collection, shatters the historical silence on home-making—in other words, the lack of information about the customs and tasks that made the family’s existence and subsistence possible. It also illustrates the dichotomy between paid labour outside the home and caregiving labour in the privacy of the home. That historically ignored private life between four walls shaped the concept of intimacy that has endured to this day: the home is still considered a predominantly female domain, although this idea is gradually fading thanks to efforts to revisit and revise that notion.

Nicolaes Maes

The Naughty Drummer

ROOM 25

This painting recalls the days when childcare was a job for women, whether or not they were the children’s biological mothers, and their duties included correcting inappropriate behaviour, often by using force. Subtly yet drastically, this scene depicts the punishment of a small, noisy child who was about to waken his younger sister and has been scolded and perhaps even struck with the switch the mother holds in her left hand. At the same time, we see that one of his drumsticks has fallen to the floor. The child wipes away a tear while his sister rests in a corner, barely touched by the sunshine flooding the room. The highly gestural figures of mother and son are the protagonists of this turbulent scene, which contrasts with the quiet atmosphere painted by De Hooch.

In those days, the mother’s use of corporal punishment would have been considered irreproachable. In fact, raising children with a firm hand positively reinforced the woman’s role within those four walls; it confirmed her as an authority figure, rather than prey to the supposedly inherent weakness of Eve’s descendants.

This canvas also raises a question about motherhood in connection to the central theme of this tour: Why would a woman need a room of her own, a place only for her, if her personal development and self-fulfilment is found in caring for others? To put it another way, do women assert themselves in their own right, or is maternity what gives their lives purpose? If we take away motherhood, what roles can they play?

Throughout this tour we find female figures in a variety of poses and situations, but how many and which of them do we assume are mothers? Which ones have that status? Throughout history, motherhood has not only been considered a state of grace or the result of a divine decision; it has also served to distinguish between different “classes” of women, upholding the “mother” as an example of supreme dignity and worth whose fulfilment nullified or somehow disguised the search for or attainment of her own subjectivity, while simultaneously disqualifying her from pursuing a profession or owning assets.

François Boucher

La Toilette

Not on display

For the first time in our itinerary, here we encounter what might be considered an apartment reserved for a woman’s private use. The scene depicts one of those casual, leisurely moments that Boucher loved to paint. In fact, the theme is a woman at her toilet, a private ritual hidden from the eyes of men (like the childbirth discussed earlier in Jan de Beer’s Birth of the Virgin) which was nevertheless portrayed almost obsessively by male artists. The toilet as a motif is not directly related to a bath or explicit nudity, particularly not in the Rococo period, although this was often the case during Impressionism. Instead, it refers to the rituals of washing, grooming and attending to one’s appearance that were required to conform to society’s expectations of women at the time. It was an act in which a woman adorned and fitted herself with corsets, lace, petticoats, satin, garters, feathers and jewellery. A woman did not just get dressed; she conformed. Here, the male painter’s perspective embellishes the depiction of something he is not generally allowed to see, thereby introducing a voyeuristic element. This act of “powdering one’s nose”, as Woolf put it, is what painters portrayed in their pictures as “women’s rooms”, personal spaces in which to beautify themselves. It is yet another example of the surrender— or abandonment, depending on your perspective—of women to the exclusively sensible realm, within the sense-versus-sensibility dichotomy so reviled by subsequent modernity.

If this image were reversed, we would find it odd to see a male figure at his toilet, preparing to bathe or dressing, and we probably would not interpret it as a moment of introspection or space for self-affirmation. As the next work will show, in the world of men, time dedicated to oneself was a more solemn affair.

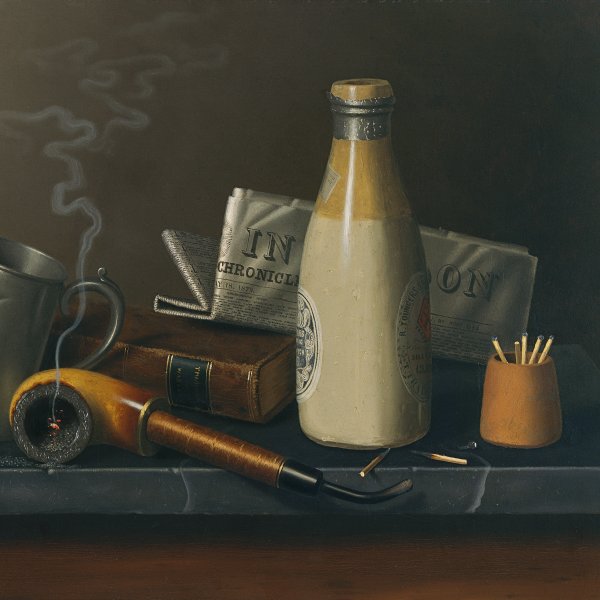

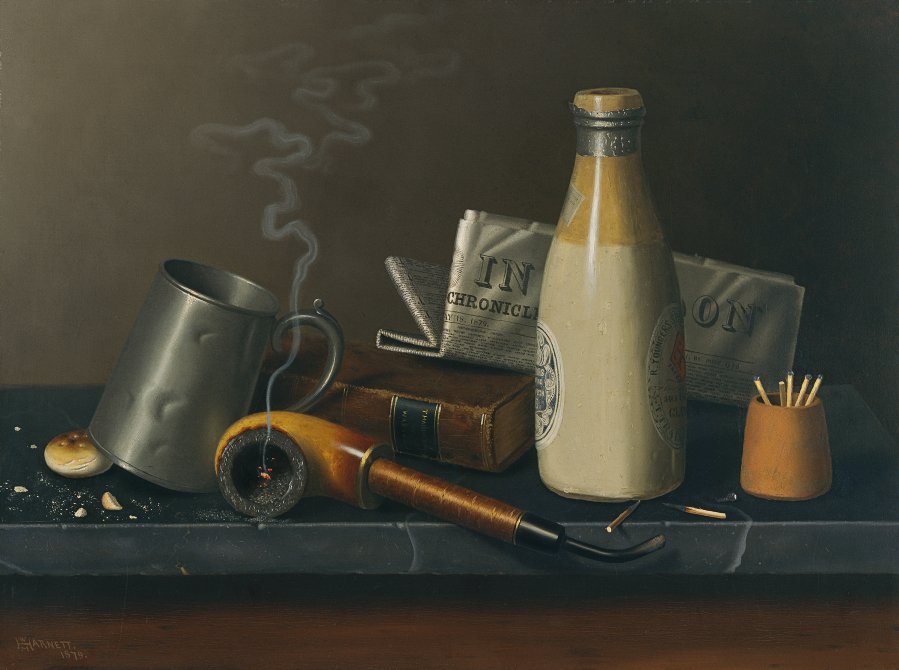

William Michael Harnett

Materials for a Leisure Hour

ROOM 32

Unlike the other selected works, this still life invites us to stop and observe certain objects. Rather than a room, it shows an action materialised and narrated by the things on display. They are traces left by a male presence, whose power legitimises that time of intellectual pleasure, absorption and solitude. What kind of objects might have been chosen to portray a woman in that context, if she had been deemed worthy of it? Probably not a jug and bottle of beer beside a newspaper, a book, a smoking pipe and a nibbled biscuit. They would more likely be—as we saw in the previous painting—personal toiletry and cosmetic items or objects for prayer, elements that defined and fixed the gender roles we still identify and perpetuate today. In fact, judging from this still life and the aforementioned work by Boucher, it seems that men read, drank and smoked in their free time, while women safeguarded the ideal of beauty, almost as if they had a monopoly on their respective pursuits.

Eugène Delacroix

The Duke of Orleans showing his Lover

ROOM 29

This canvas depicts an episode narrated in the Histoire des ducs de Bourgogne by M. Barante, which tells how the Duke of Orléans showed the naked body of his lover, Mariette d’Enghien, to her husband, his former chamberlain Aubert le Flamenc. The duke showed everything but her face, inviting her own husband to guess her identity, but he failed to recognise his wife’s body.

This canvas, perhaps better than any other work in the collection, reflects the relationship between the female body and its commodification. The women for whom both men are competing is situated in the centre of the picture between them, with her back turned to us, while one admires her and the other exposes her naked form. Here the nude body is portrayed as a commodity, pointing to one of the other tasks assigned to women: that of satisfying the desires of others. From our perspective, the hand that conceals her face with a sheet, as part of the story told in Barante’s text, takes on new meaning, signifying the woman’s anonymity. We can just barely make out the profile of her timid, bashful countenance, but her face is hidden, leaving us to guess her identity and, if we cannot, condemning her to remain anonymous. The sheet acts like a wall, making it impossible to identify and accurately portray the person, who is therefore presented to us as a body intended for another’s pleasure.

Berthe Morisot

The Psyche mirror

ROOM 33

In the lecture that serves as our guide through these rooms, Virginia Woolf said, “Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.” Now, in this work by Berthe Morisot, we see a young woman in a private room standing before a mirror, whose attitude is diametrically opposed to that of the lady in Boucher’s La Toilette. The model’s gaze and her reflection are intended to please no one but herself. The act of admiring oneself in a mirror entails a degree of self-absorption that recalls the myth of Narcissus and hints at elements of subjectification that differ from traditional portraits intended to show the viewer admirable qualities. The girl is shown in profile, lost in thought. The artist caught her in the act of acknowledging and asserting her own body, a very different attitude from that of a model posing for a male painter. In this scene she poses only for herself, though her role is still that of the “beautiful object”, the secret to the success of female portraiture in a patriarchal society that has traditionally personified Vanity as a woman gazing into a mirror.

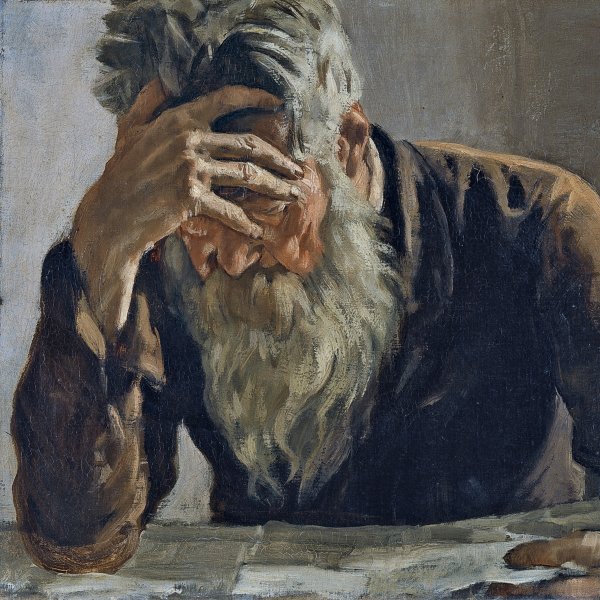

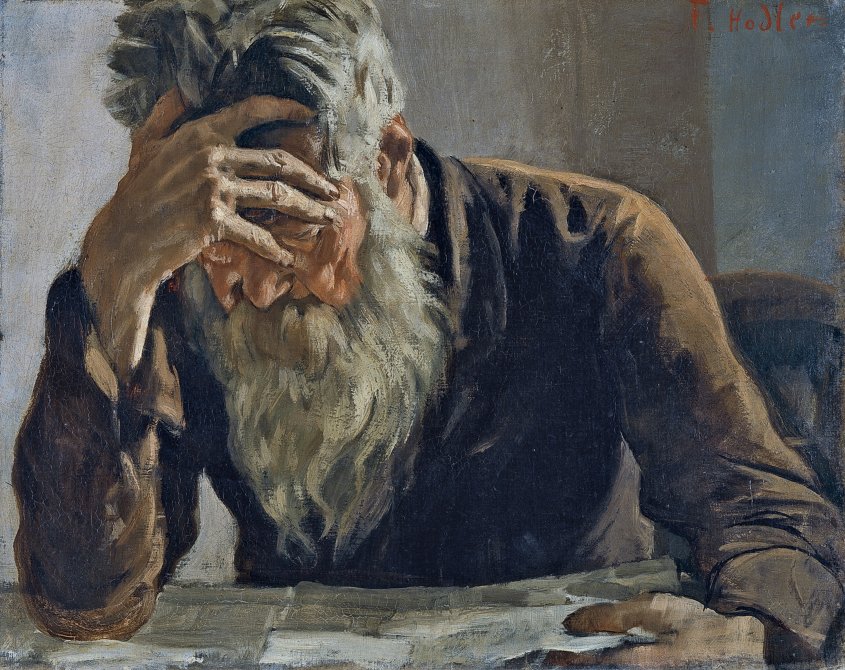

Ferdinand Hodler

The Reader

Not on display

This canvas by the swiss symbolist painter Ferdinand Hodler evokes the place of reading, which our culture conceives as an interior space of individual activity. There is something inimitable and absolutely intimate about the act of reading, something that painters have striven to capture but can only be glimpsed through depictions of readers. As Guillermo Solana noted in his catalogue for the exhibition Heroínas (2011), reading is constructing a room of one’s own, a way of developing one’s identity and, in the case of women readers, so frequently portrayed in the history of Western painting, an attempt to live vicariously through the lives of others, at least in the case of novels. The reader’s still pose naturally lends itself to painting, but it also has a certain theatrical quality, as if the brushstrokes might let us re ad what the person is reading. In this picture, we know the subject is reading a newspaper, and although we cannot make out its contents, we undoubtedly identify a certain affection in it. This male portrait is a veritable tribute to that theatrical rendering, the externalisation of reading.

The expressive brushwork captures the monumental burden of the passing years, drawn in the man’s wrinkles and white hairs, and directs our gaze to the newspaper resting on the table on which his eyes are fixed; the reader’s hand conceals his gaze from us, as if attempting to shut out the rest of the world. The main theme is therefore the glorification of the “self”, understood as the exaltation of subjectivity rather than an embodiment of moral rights and duties that justified the relevance of a portrait based on the sitter’s social status, as we have seen in other works on this tour. On the contrary: this sitter is moved, he “somatises” the reading.

Literature, biographical or otherwise, always entails a degree of self-referentiality; it rests on the very concept of the subject, someone who has something to say and needs to put it in writing. The same is true of visual representations of workplaces. Practically every aspiring artist of the last four centuries painted his or her workshop at some point as a correlate of their subjectivity, a kind of self-portrait. Showing oneself through a room of one’s own has a narrative component, for that “ownness”—ownership—confirms character, secures dignity, and attests and delimits a subject’s place in the world. In short, ownership determines the process of subjectification. Its absence, as in this case, places us in a vulnerable, indecisive limbo where words are not written down and brushstrokes fail to dry, where we glimpse anonymity.

Henri Manguin

The Prints

ROOM H

Like many of the other selected pieces, this work is set in a private room occupied by two women who, in this case, are looking at prints. It almost seems as if we are seeing double, for the figures, one naked and the other soberly attired, represent the same person: Jeanne, the painter’s wife. In an instructive or indoctrinating attitude, suggested by the dark dress that stands out against the colourful background, the clothed woman seems to be teaching her nude counterpart, watching her as she rests the coloured prints on her lap. Meanwhile, the naked Jeanne looks straight at the prints in foreshortened perspective, turning her bare back to us. The choice of pose and its prominence within the scene is an obvious tribute to Ingres’s Turkish Bath, a quintessential example of voyeurism.

Both versions of Jeanne, absorbed and focused on the task at hand, seem to complement each other, illustrating what the painter perceived as different facets of his wife. The naked woman is entirely receptive to the art before her, focusing her attention and her gaze upon it while nonchalantly showing us her nude form. The dressed woman “shows” whereas the naked woman “shows herself”. We might think that Manguin duplicated the model here as a kind of tribute to his wife’s different facets, the intellectual and the sensitive side. However, it is more likely that this double portrait has no significance beyond mere visual formalism, and that in painting her nude, the painter was once again comparing the female silhouette to a beautiful object in a kind of arabesque—like the prints she is holding, which contrast with the profusely and colourfully decorated room.

Even so, we still see the scene (as in Boucher’s case) as an example of a pictorial print in itself, summarising the conventional male perception of female identity as a projection of their own desires. As Woolf concluded, “Indeed, if woman had no existence save in the fiction written by men, one would imagine her a person of the utmost importance; very various; heroic and mean; splendid and sordid; infinitely beautiful and hideous in the extreme; as great as a man, some think even greater. But this is woman in fiction.”

Georgia O'Keeffe

New York Street with Moon

ROOM J

We've already surveyed more than four hundred years of history in these rooms, and so far most of the highlighted pictures have exhibited the voyeuristic tendency of men to embellish female imagery. We have also seen the narrative use of common rooms, where the tasks of keeping house and caring for family manifested the virtues of women as wives and mothers.

It may therefore seem odd to find ourselves before the image of a street. In 1925, a woman painter dared to portray the street. We included this work because it clearly exemplifies the attempt to claim not only a private life but also a public one, a life common to all city-dwellers, men and women alike, outside a house or a domestic interior. This canvas represents the struggle of women to participate in public life in the early 20th century and have an active presence in the public space, as Deborah L. Parson and many other feminist authors have discussed.

For a woman to portray a city was a bold act at the time. Georgia O’Keeffe herself was sharply criticised for wanting to capture the impressive streets of New York City in her work. Her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, was opposed to the idea of including this picture in her solo show at Anderson Galleries in 1925 because the setting and theme were supposedly too masculine. Instead, he suggested that she exhibit oil paintings of enlarged flowers, deemed more appropriate and feminine. One year later, O’Keeffe managed to include it in her show at The Intimate Gallery and sold it on the first day for one thousand two hundred dollars. “From then on, they let me paint New York,” the artist remarked.

Edward Hopper

Hotel Room

ROOM 45

As the epilogue of this selection of works, we find ourselves facing a solitary female figure in a hotel room, painted by Edward Hopper in 1931. Two years before this painting was made, Virginia Woolf delivered the lecture that inspired this thematic tour to the Newnham College. Its existence shows that the art scene of the day was already beginning to rethink and question the role of women in the public and private sphere. In addition, artists were starting to view hotels and other transitory places like airports, restaurants and stations as interesting settings. For Hopper, those briefly occupied spaces were ideal for capturing the spirit of a generation that experienced the constant loss of emotional ties.

The image of this woman sitting on the edge of the bed conveys an unsettling feeling of loneliness, a constant in the American painter’s oeuvre, which also lacks the conventional accessories associated with female imagery that we saw in the other works. In underclothes, she holds a train timetable in her hands. We only see the profile of her face, with no identifiable expression, underscoring the artist’s need to speak to us of anonymity. The absence of decorative elements confirms the perception of an empty, impersonal space, and the vertical lines that frame the room are overpowering, leaving us before an inert boxed-in form that exudes a vague narrativity.

Almost all of the domestic spaces we’ve seen on this tour have a slightly impersonal feel, but that impersonality is more solemn in a hotel room, designed to house a few fleeting moments of life. Many later artworks have focused on transitory places where we leave something of ourselves. Exploring those traces we leave behind, and in dialogue with this canvas, in the 1980s Sophie Calle created a remarkable photographic series in which she compiled “incriminating” evidence in four-teen hotel rooms in Venice (L’Hôtel). She, a woman, became a voyeur and detective of the intimacy woven there. In addition to photographs, the artist produced a written record, almost like a police report, of the facts that can be gleaned from the vestiges and objects found in those rooms. Her work may be a tribute or response to Hopper’s, but unlike him, Calle accompanied it with exhaustive documentation in an attempt to avoid anonymity and vagueness. We could interpret Calle’s work as a woman artist’s attempt to appropriate the narrative, to be the subject of the plot— in other words, to be the one who gives meaning to those rooms, appropriating their potential history.