By Mariola Campelo Tenoira

The itinerary Art and Sustainability. Social Challenges from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection is conceived to encourage sustainable thinking with the permanent collection of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. Throughout the itinerary, visitors will notice that the works have been selected based on aesthetic-experience criteria interrelating art and sustainable development in terms of ecology, economy and society. To that end, a group of paintings have been brought together to be reinterpreted within a framework under which empathy with environment and sustainability may be generated. These works are not to be considered environmental art but masterpieces of art history allowing links between cultural production, society and sustainable development to be considered from a historical point of view.

This guide is conceived as a resource for self-guided visits by the public and allows exploring the three levels of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and learning about some of the most representative works of the permanent collection.

Tour artworks

Claude Lorraine

Pastoral Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

Not on display

Claude Lorrain (born Claude Gellée) was one of the earliest artists in history to concentrate on landscape as an autonomous pictorial genre. In his paintings, nature became landscape, a segment of nature extending as far as the human eye can see. Born in France, Lorrain undertook a large part of his artistic trajectory in Italy, primarily in Rome, and by the end of the 1630s had acquired considerable standing as a landscapist there.

Lorrain grew out of a tradition of landscape painting by northern artists settled in the Eternal City that were interested in ruins as an artistic motive for their drawings. As well as those, Lorrain was inspired by the Roman Campagna, a natural site outside the city, and approached it with genuine aesthetic admiration. The painter was not very interested in the subject matter of his painting, here the Flight into Egypt, which he brought to his present by inserting into Bible times daily Roman landscape scenes of his time.

Most likely because his clients were erudite lovers of Roman culture, Lorrain’s painting ‘deals with religion’ but is not religious (figures will gradually disappear from the scenes to become insignificant in his landscapes). Landscape is a setting for reaffirming (moral) values related to mythological scenes or the historical question. However, his idealised depictions stem from invention. Claude Lorrain does not merely paint the Roman countryside topographically. The light he uses streams in through the scenes with a natural effect providing the picture with serenity and poetic significance. Furthermore, the artist fuses in his landscapes the different Italian cities that he had visited (Naples, Capri, Civitavecchia, Genoa, etc.) Architectural ruins recall in his painting the golden age of the time when Aeneas disembarked and founded Rome, as described in Virgil’s poems, triggering a feeling of nostalgia for the lost greatness.

Even though these images show us an idealised and aesthetised look about nature, Lorrain’s landscapes still evoke a harmonious relationship between culture and nature, an encounter that amounts to living in nature instead of from nature and requires for societies to commit themselves to the protection of cultural heritage and the preservation of environment for the purpose of reducing climate change.

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

The Grand Canal from San Vio, Venice

ROOM 17

Since its establishment, Venice’s history has been linked to water. In the 5th and 6th centuries, the natural lagoon on which it lies served as a refuge to those peoples who fled from Barbarians. Then, the first palafittes were erected, the islands were widened and the lagoon was drained, thus the famous canals were born. Its unbeatable location provided a successful economic development related to marine technologies and East-West trade. Wealth accumulation turned Venice into a sophisticated city and this was particularly reflected in its splendid historical and artistic heritage. With the emergence of new maritime routes towards the New World, the ‘Serenissima’ took an economic and political downward turn. However, the carefree Venetian social life still continued, as it was possible to enjoy parties (carnival), theatre shows and amusement aimed at attracting foreign visitors to the Lagoon.

This complex urban and social reality is at the root of the veduta, a cityscape pictorial genre that became particularly relevant with Canaletto owing to his ability to integrate urban structures and life. In The Grand Canal from San Vio, Venice, the Italian painter chooses an elevated place and focuses the perspective on San Marco to show with topographic accuracy sites of interest in Venice while including the atmosphere of the city’s busy or idle inhabitants. However, Canaletto employs invention. In his images, Venice remains unchanged over time. The sun is always shining in his pictures, as if Venice was perpetually smiling to its visitors.

The veduta were very sought after by travellers and art lovers who completed the Grand Tour. A germ of modern tourism, this long journey through France and Italy was in the 18th century an essential step in the education of European aristocrats, who found in these views the ideal souvenir of their youth adventure. Tourism is today the driver of Venice’s economic growth, a practice involving a highly specialised services sector. This urban development model has brought short-term benefits for the local economy but, at the same time, rising house prices and unemployment have pushed its inhabitants towards the city limits. Alongside climate change, which has increased the Adriatic Sea level and led to more frequent acqua alta events, the poor management of a mass and uncontrolled tourism is negatively affecting the protection of cultural heritage and threatens the sustainability of a key economic sector of its economy.

Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael and Collaborators (?)

Winter Landscape

ROOM 28

Dutch Golden Age Painting showed a great production of works aimed at decorating the civil buildings of a new nation independent from the Spanish empire as well as the homes of a prosperous middle class who had benefited economically from the Dutch maritime and commercial supremacy in Europe. Specialisation becomes crucial in this context of great artistic activity. Among others, landscape painting became in Holland a separate genre, and winter was a very recurring theme. Jacob van Ruisdael depicted, with a clear naturalistic sense of daily issues, this harsh season where life comes to a standstill and keeps pace with nature.

The availability of a fossil fuel energy source was essential in these circumstances. Two opposing types of sources that contributed to economic development in the Netherlands coexist in our picture. A number of warehouses for peat, a fuel that was transported by boat, can be found at the bend of the iced canal. Peat is a fossil energy that was intensively exploited in Holland because it had low production and distribution costs thanks to the country’s vast wetlands and the development of a wide network of channels for transport. It thus became a national economic pillar, supplying the high demand for energy of the growing urban centres but, at the same time, posed a threat to land and agricultural fields due to the aggressive underground operation techniques required.

A wind-powered mill that produces inexhaustible and clean energy appears in the background. Holland developed a strong engineering of mills, now integrated in the country’s industrial landscape, for a wide range of uses. Sawmills for shipbuilding and water-powered mills, used to drain water from coastal areas below sea level suffering from incessant floods, are possibly the most outstanding examples.

The scene showed in our picture may help us reflect on the type of economy we want to adopt in order not to exhaust the planet’s energy resources. We human beings must now consider a transition from the use of fossil fuels towards renewable, clean and inexhaustible sources of energy that do not result in greenhouse gas or pollution emissions harmful to the planet and to our health.

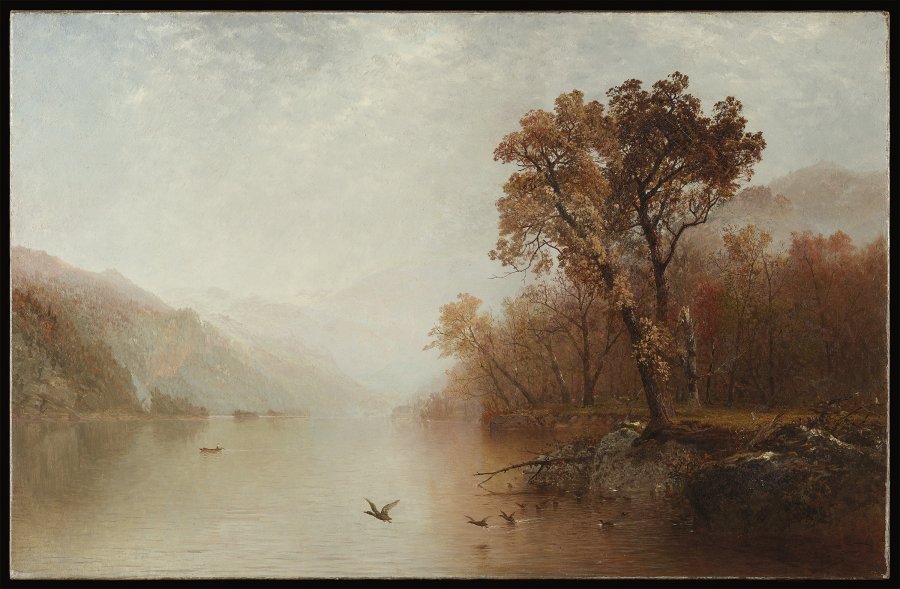

John Frederick Kensett

Lake George

ROOM 32

In the aftermath of the American war of Independence (1775-1783), the United States nation begins to form. Painting will play a fundamental role in that process of identity construction. Landscape art was of particular importance in shaping a social awareness regarding a vast and still largely unexplored territory.

John Kensett was a member of the second generation of the Hudson River School landscape painters. This School was embodied by a group of North American artists that travelled to Europe to absorb the Old Continent’s pictorial tradition and develop a ‘truly American scenes’ painting upon their return. Back in the United States, Kensett’s painting expresses a sublime harmony between the American landscape and its inhabitants, with nature as a comfortable and peaceful place for people.

Kensett had visited Lake George, the largest one in the Adirondacks (northeast of New York) in 1830 and sketched its wild mountain range and the region. The location, time of day and atmospheric conditions were carefully selected by the artist in order to portray the scene isolated in time and space.

As former Flemish painters did, he works thoroughly on details and uses delicate brushstrokes, subtle tonality modulations and a balanced composition in order to capture the calm, silence and serenity of the natural site. The flight of birds is a symbol of harmony; the continuous horizon lends a sensation of stability to the landscape and evokes the vastness of North American land.

Everything in Kensett’s luminist painting takes us to an untouched place which is not free of historical associations. Lake George had been an emplacement of several military campaigns during the wars against the Indians and the French (1755-1763) as well as during the American Revolution (1775-1781), and James Fenimore Cooper would make it the setting for Last of the Mohicans (1826). In the 1850s it became a tourist site as a result of the arrival of railway.

Thanks to the artists that depicted landscape as a general value for the (North) American nation, the government took conservation action to protect natural sites. The United States created its first national park (Yellowstone, 1872) a few years after this painting was undertaken, which suggests a close relationship between such an aesthetic awareness and the conservationist spirit regarding ecosystems of unique and inimitable wealth.

Caspar David Friedrich

Easter Morning

ROOM 29

Against a relationship with the environment based on occupation and conquest, German Romanticism showed a contemplative attitude towards nature by human beings. Landscape became the romantic genre par excellence. It embodied all new aesthetics and was the form of artistic expression ideal for capturing the artists’ individual emotions. To do this, painters come into contact with nature and leave the studio to sketch nature outside. They go thus beyond an excessively idealised view of nature and make a spiritual and emotional link with the landscape.

For Caspar David Friedrich, art played a mediation role between an impressive nature and human beings that feel simultaneously overwhelmed and attracted by it. Friedrich used to go outdoors and observe nature; his paintings indicate the artist’s focus on the local level, as they are a synthesis of the German landscapes he visited. Even if descriptive, Friedrich’s landscapes sought to go beyond landscape’s topographical elements.

Everything in this Easter Morning takes on a deep spiritual interpretation: groups of three women are walking slowly towards a cemetery, suggested by the milestones along an infinite path, an Easter morning on which nature celebrates its awakening, as shown by green buds on the tree branches. Also, and together with the sun (a symbol of rebirth, of return to life) guiding the women, the green buds in this painting symbolise the revival of a nation: the German nation, liberated from the French occupation that had so much affected the painter emotionally. Friedrich succeeds in giving the landscape a symbolic dimension through which he connects with the spectator. The backwards figures, characteristic in his paintings, serve as a component of involvement and mediate between the landscape and the spectators (of the picture), as they face the view as if it was a window on the world, just us we face the picture.

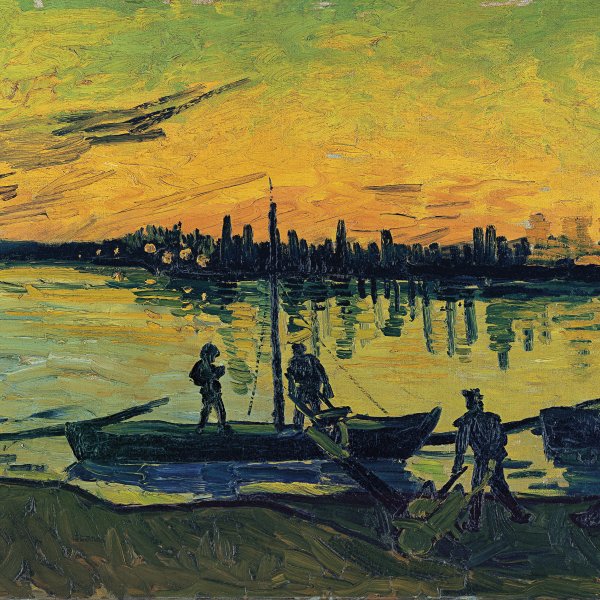

Vincent van Gogh

The Stevedores in Arles

ROOM 34

Vincent van Gogh arrives in arles in February 1888. The Dutch artist expresses in his paintings the strong impact that the light in the French Midi, a region of southern France along the River Rhone, had on him. And he does it in an increasingly synthetic style, using stronger brushstrokes and deep pure colours that will now feature his painting. In this piece, Van Gogh captures the vibrations of dawn light on the river and the coal unloaders’ efforts. He still continues to take an interest in the working classes’ world.

The city of Arles is closely linked to the exploitation of the Rhone’s water. Its wealth and prestige are in keeping with periods of heavy exploitation of the river. The Rhone is the sole waterway connecting the Mediterranean with northern Europe, and has since ancient times been a major axis for movements of people, cultures and goods, as well as an element that structures the territories through which it flows. Before roads and railways were developed, it was used as an inland route connecting the cities of Arles (a former imperial town), Avignon (a papal residence in the Middle Ages), Valence, Vienne and Lyon with the French Mediterranean ports. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution turned the Rhone into an artery between the riverside industrial districts. Arles recovers then its role as a meeting point between river and maritime navigation. However, the construction of the railway Avignon-Marseille puts an abrupt end to the economic boom of this river port. When Van Gogh painted The Stevedores, Arles port was merely the place of departure and destination for the coal distribution service.

Today, much of the economic activity of the cities grown on the Rhone banks is still based on the power of river’s water. The Rhone is now an important source of renewable energy thanks to the dams that were built on its bank and produce 20% of the hydroelectric power in France. The current management of the river seeks to reconcile social development and water physical and ecological integrity.

André Derain

Waterloo Bridge

Not on display

Industrial development and the resultant transformation of cities is rejected and admired to the same extent by modern artists. London will be one of the most seductive models, and very popular with artists such as William Turner. Following the artistic and commercial success of the series that Claude Monet had dedicated to this city some years before, art dealer Ambroise Vollard commissioned André Derain a suite of views of the trendiest city. London, the capital of the vigorous British Empire led since 1800 the course of Europe’s economic and industrial development. It was the greatest city in the world and continued to grow throughout the 19th century.

Economic prosperity had a substantial impact on urban space. New industrial areas were developed and their architectural landscape included new manufacturing centres. However, the refined government institutions and life improvement for the middle classes came along with overcrowding problems for the working classes. Wet climate, factory smoke and coal soot, as well as wastewaters directly discharged into the River Thames caused the 1958 plague. A new sewer and wastewater treatment system that is still a reference in urban infrastructure will then be planned.

The redevelopment of the Victoria Embankment, which transformed it into an avenue to facilitate the traffic flow in this Thames riverside, was a model work in the 1860s. André Derain chose the view from that place to paint this picture. The fauvist painter (fauve means wild beast in French) follows Claude Monet’s topographic tour. However, unlike the latter, that captures London’s fog and mist, Derain uses divisionist brushstrokes as well as sharp and pure colours to shows us an unknown brightness of the capital city.

In Derain, the signs of industrialisation and the governmental or historical elements have the same relevance in urban landscape. In this open view from the Victoria Embankment, Derain looks over Baltic Wharf’s industrial buildings including the Shot Tower and some factory chimneys; the Victoria Tower of the Parliament building is behind it and, right in the centre, the obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle which was brought from Egypt stands on the bridge; further to the right, the Whitehall Court takes a mountain-like shape.

The French painter sets both the noble and industrial parts of London at the same visual level in a single silhouette dividing the landscape’s natural elements: sky and water. The strong sun in this view of Waterloo Bridge casts however its powerful rays on the city and dazzles it. It seems as if Derain had wished to paint simultaneously a promising and apocalyptic vision of London, of modern cities.

Sonia Delaunay

Simultaneous Contrasts

ROOM 42

Sonia delaunay was an expatriate Jewish artist that arrived in Paris in 1905 after receiving a quality cosmopolitan education in Russia and Germany. She approached quickly the most avantgarde artistic circles in the capital city. In 1908 she met Robert Delaunay, whom she later married and with whom she held a very fruitful artistic exchange that resulted in the so-called Orphism. They jointly sought to reproduce the pace of modern life and, under the same theories on light and colour denominated Simultaneism, they arrived at abstraction in different ways. Sonia quickly recognised the limitations of painting to capture movements and the dynamic interaction of shapes and colours, and decided to experiment with tissues; her first purely abstract creation was a patchwork crib quilt she made for their son Charles, born in 1911, reminiscent of traditional Russian quilts.

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum’s Simultaneous Contrasts follows the orphistic logic of her first works, such as the above mentioned quilt: as if they were remnants, the artist ‘makes’ the different planes of this abstract picture and differentiates them through the contrast between complementary and discordant colours, such as blue and red, which vibrate beside each other.

Thus, by experimenting with fabric design and applying her results to painting, Sonia did not only find a way to reflect the dynamics of modern life, but also succeeded in eschewing the traditional distinction between the fine arts and the applied arts, a gap that the most radical avant-garde movements such as Dadaism and Futurism also tried to overcome. Her models met with great commercial success and for a short period of time she abandoned painting and devoted herself completely to design and the applied arts, since this work brought the economic well-being the family needed.

However, the critics at the time never considered Sonia as a complete artist, in opposition to the significant artistic recognition gained by Robert, as he was deemed to make ‘art’ and she was deemed to make ‘handicrafts’; supposedly, he worked on formulating aesthetic theories and she applied them to the decorative arts. It was only in 1987 that their productions were combined in an important exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

Sonia Delaunay embodies the difficulties that women still face to be recognised as key actors in the development of our societies. In the quest for sustainable development, it is essential and necessary for us to socially, politically and economically recognise the hidden work carried out by women throughout history.

Natalia Goncharova

The Forest

ROOM 43

Natalia Goncharova was part of a group of Russian artists that recovered folk art aiming to incorporate it into the avant-garde experiences of Rayonist (ray of light) abstraction. Also, she was one of the Russian Amazons, the name under which the poet B. Livshits brought together six women artists (Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Alexandra Exter, Varvara F. Stepanova, Olga Rozanova and Nadeshda Udaltsova), with strong personalities and heterogeneous creations, that advocated for equality with their male colleagues in the field of art creation and received recognition of their leading role in the Russian culture. Goncharova, together with Mikhail Larionov, will live as an expatriate in Paris since 1919 and will not take part in the Russian Revolution, as some of the Russian Amazons artists did.

With Larionov, she developed Rayonism, a painting style based on the study of the expansion of light proceeding from several sources. This painting shows us a whole battery of rays represented in all directions that make it possible for the object and the scene to be observed and allow us to penetrate into this thick abstract landscape. Rayonism has a thematic background and figures are not completely abandoned, but it opened the door to abstraction for Russian art. Equating arts with crafts was an important factor in the development of the Russian avant-gardes and also played a central role in achieving a balanced consideration of men’s and women’s production.

A large share of Goncharova’s oeuvre is devoted to the countryside where her wealthy family was from. The aesthetics in The Forest are close to the lubki, the woodcut folk tales carved in wood that decorated Russian peasant families’ homes. Thus, this painting’s technical work and the evocation of forest bring us within this ecosystem, a lung of the Earth that is threatened today by deforestation.

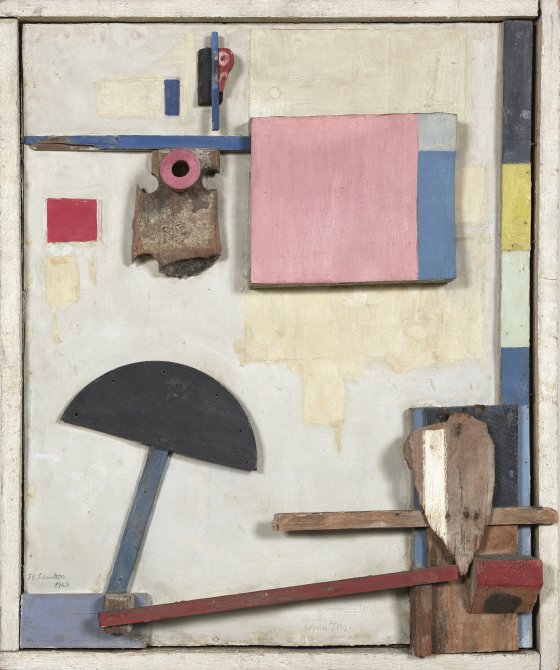

Kurt Schwitters

Merzbild Kijkduin

ROOM 44

Kurt Schwitters was one of the most radical artists in German Dadaism. He used to vehemently assert: ‘I’m a painter and I nail my pictures together’, a complete protest against the values of art and traditional painting. Breaking with all artistic standards, he created his undisciplined Merz (assemblages carried out with different technical resources) with most crazy materials found anywhere. The term Merz was taken by chance after a fragment of the word Kommerzbank (a major bank in Germany) in a bank receipt and reached its highest point with his masterpiece Merzbau (1923-1932), a sort of column destroyed by a bomb during World War II to which Schwitters every day added —like a sort of diary—randomly found objects that had drawn his attention.

Merzbild Kijkduin is an assemblage undertaken in the Netherlands during the ‘Dada Tour’ made by Schwitters and other artists in 1923. The word Kijkduin is the name of a small seaside village near The Hague. By its seashore, Schwitters harvests wood and waste carried by tides. In this work, the chaos of Dada’s chance dialogues with a constructivist order, distributed in two rhythmic parts that divide this still life.

Schwitters rescues randomly and neatly combines in his pieces those objects disposed of by the (consumer) society because they no longer serve or because they have served their purpose, reusing them and providing them a new existence in the artwork. This act of rebellion against the traditional way of artistic creation could now be interpreted as a form of recycling. Instead of creating out of nothing, the Dadaist artist reuses and recycles waste materials and turns them into art. From today’s perspective, Schwitters’ work invites reflection on a reduced consumption and the usefulness cycles of material goods. Compared to the philosophy of disposable linear consumption, the artist collects wastes at the end of their service live and transforms them into resources, that is, products are taken from cradle to cradle as a principle of circular economy.

Mark Tobey

Earth Rhythms

ROOM 46

In the aftermath of the armed conflicts that destroyed de Enlightenment values of modern Europe, the North America painting of the second half of the 20th century removed the contradictions of reality from its content and came back to abstraction in order to focus on the expression of the existential distress of the human condition.

A nomadic and cosmopolitan artist, Mark Tobey pioneered Abstract Expressionism in the United States and research on oriental calligraphy and ink drawing. His ‘white writing’ is an expression of several visual cultures and his painting style, delicate and linear, stems from nature observation as well as from Surrealist automatism and Oriental mysticism, which influenced him since his journey to China and Japan in 1934.

He learns and handles oriental calligraphy even if his own writing is primarily occidental. For this American painter, lines are an expression of the easternmost tradition and mass is the result of western culture. In this painting, mass is an all-over in earthy tones, with light touches of red, blue and purplish threading their way through a number of floating white calligraphic lines that create Tobey’s personal spatial representation of cosmos.

Devoted to small size works, Tobey’s guiding theme is the swarming movement of crowds on city streets. However, Tobey does not portray urban chaos but the (white line’s) rhythm that frees the individual from the crowd and from urban distress. His subject is the artist’s microcosm, his experience in the city, what is happening there.

Mark Tobey’s painting is a field for reading, for open reflection. He ‘writes’ his pictures with the calligraphic rhythm of never-closing white lines that organise the balance of the composition as a constellation of forms, signs and presence. Tobey’s meditative study of nature goes beyond a traditional western contemplation and penetrates into biological rhythms. In a metaphorical sense, the universality of his themes turns this painting into a welcome excuse to talk about the urgency of listening to the earth’s rhythms and respecting now the limits of the planet in order to guarantee the sustainability of (the needs of) future generations.

Romare Bearden

Sunday After Sermon

ROOM 48

The presence in the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum’s collection of the work of an African American artist offers us an opportunity to talk about social equity and recognition of other cultures within the historical account of western art, these being among the key factors for sustainable development. Romare Bearden was born to a wealthy African American family that took an active part in Harlem’s cultural renaissance beginning in the 1920s, and grew up in contact with poets, painters and musicians.

While studying educational sciences at the New York University, from which he graduates in 1935, he takes evening classes under German painter and awareness raiser George Grosz at the legendary Art Students League. Perhaps under Grosz’s influence, his first works are cartoons for activist magazines and journals that condemn racial segregation in the United States. Bearden also served in World War II and, under the G. I. Bill which provided funding for soldiers demobilized after the conflict, he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, Paris, and discovered first-hand European art.

Romare Bearden fought actively for the civil rights of black people in the United States and this concern is always expressed in the themes for his works. Along with other black artists, in 1963 he was a founding member of Spiral, a short-lived group that promoted the commitment of the ‘Negro’ artists to the African American community’s demands.

Sunday after Sermon 1969, a street scene in which several people chat in a group after the weekly church service, is a large collage combining newspaper and magazine cuttings. He uses collage to insert, in a Cubist style, snatches of black people’s realities into the pictorial surface. The artist also finds his inspiration for this picture in Dutch genre scenes (the brick building reminds us of Vermeers’s outdoor scenes). Features of western culture (collage and genre scenes) and New York City’s African American community social practices coexist deliberately and in balance in this work by Romare Bearden.