Woman and Books: A Reflection through Western Painting

Inés Alberdi. Commentaries on the works written by the departments of Old Master Painting and Modern Painting

Images of women reading or holding a book are very common in European painting from the Renaissance onwards. Books have symbolic connotations of status, knowledge and refinement.

The tour highlights works containing this image and classifies them into three groups: Annunciation scenes, Renaissance portraits, and women reading in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Images of the Annunciation.

The Annunciation is the episode in the life of the Virgin Mary where the archangel Gabriel announces to her that she is going to give birth to Jesus, and she is often depicted holding a book in these scenes. Books are symbols of both elegance and piety. Reading adds a humanistic aspect to the idealisation of Mary as an example of female excellence.

The image of a young girl reading, based on this iconography of the Virgin in the Annunciation, evokes an air of piety and virtuousness, but also of autonomy, of having free time for herself. And by extension it conveys a positive view of education for women. The iconography of the Annunciation is contradictory: the young woman’s words stress her submission and humility, but the presence of the book she holds expresses an idea of intellectual superiority and capacity.

Renaissance Portraits.

Portraits of ladies with books have a noticeable elegance that is afforded by culture and the huge importance society attaches to knowledge. Only a minority of women received an education, yet there are many portraits of women with books. Books were uncommon and were used as signs of distinction.

Seventeenth-century Dutch portraits of wealthy bourgeois merchants often feature women reading. Books hold a symbolic value because they enhance the sitters’ individual profile with an added intellectual status and the refinement that comes from knowledge.

Women reading in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries economic development and urbanisation in the European countries were accompanied by the growth of the middle classes and their culture. Women had much greater access to education and artists portrayed these new, more knowledgeable middle classes. In art this rise in women’s culture and education was reflected in an increase in images of women reading. The subjects of paintings became democratised, and many portraits were painted of middle-class women.

Numerous paintings show women engaged in everyday tasks. One of the activities chosen to represent women’s daily lives was reading. It became relatively fashionable for them to pose reading. Culture became a middle-class value. Education continued to be considered a sign of distinction, and portraits of women with books were a means of conveying this intellectual refinement.

Starts on the second floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

The Annunciation Diptych

This exquisite panel painting by Jan van Eyck is designed as a diptych and is part of a group of small works intended for private devotion. The artist depicts the figures standing on a plinth. The angel is on the left and the Virgin, on whom the dove of the Holy Spirit perches, is on the right.

The theme of the Annunciation is taken from the Gospel of St Luke (1: 26–38), which tells of the episode that took place in the Virgin’s home in Nazareth when the angel appeared to her to announce that she would give birth to the Saviour. Van Eyck commonly made inscriptions on the frames of his paintings, and here he quotes the first and last sentences of the dialogue between Mary and the angel. Other literary sources that addressed the theme of the Annunciation were the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (9: 1–2) and the Infancy Gospel of James (11: 1–3).

The Flemish master expertly conveys the sense of the mystery and purity of the scene, which is executed in grisaille. The use of black and white creates an illusionistic effect and gives the oil painting the appearance of a sculpture group. Here – as is often the case in western painting – Mary is shown reading a book identified as the Holy Scriptures. This image of the Virgin reading was disseminated during the Gothic period and expresses her intellectual capacity, which is mentioned in a few apocryphal Gospel accounts of her life. The book is considered an attribute of the knowledge of the Virgin, who meditates on the coming of the Saviour and specifically on the words of the prophet Isaiah (7: 14–15) announcing that a virgin will conceive and give birth to a son whose name will be Immanuel, meaning God with us.

The Annunciation

This small panel depicts the annunciation episode described in the Gospel of St Luke (1: 26−38). Bonfigli illustrates the moment the archangel Gabriel appears to the Virgin to announce that she will conceive a son by the power of the Holy Spirit.

The child will be called Jesus and will be the son of God. Through a beam emerging from a parting in the heavens God the Father sends down the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove with two flames. The presence of the dove, positioned in front of the kneeling young Mary, underlines the mystery of the Incarnation referred to by Luke: ‘The Holy Spirit shall come upon you, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow you: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of you shall be called the Son of God’.

The iconography of this passage is inspired by various apocryphal sources. Compared to pre-Gothic compositions, where the Virgin is depicted seated on a throne and spinning, Bonfigli adopts the by then widespread formula of the Virgin meditating with a book on the prophecy of Isaiah (7: 14–15), which Luke included in his Gospel.

The Virgin kneels with her hands pressed together in prayer. She is not holding the book in this composition; instead it lies open on a lectern. The books piled on two shelves beneath it indicates that her reading is not limited to the prophecy of Isaiah.

This scene does not take place in a loggia or closed architectural structure but in an open space, though it is fenced off by a wall that separates the figures from the background landscape. This setting closed to the outside world may be a reference to the hortus conclusus, a further allusion to the Virgin’s purity taken from the Song of Songs (4: 12): ‘A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse, A spring shut up, A fountain sealed’. The lilies held by the angel are a symbol of Mary’s purity, while the vase of red and white flowers between them is a reference to the future Passion of her Son.

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

This masterpiece from the collection is an outstanding example of portrait painting in Quattrocento Florence. Both the circumstances surrounding its com- missioning and the sitter’s identity and life are known thanks to surviving records from the period.

Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni married Lorenzo Tornabuoni in 1486, but died of unknown causes during her second pregnancy two years later. Lorenzo, greatly saddened by his loss, wished to immortalise his beloved in a picture and com- missioned Domenico Ghirlandaio to paint her likeness. It is a posthumous work for which the artist used a full-length portrait of Giovanna in the Visitation fresco of the main chapel of Santa Maria Novella.

Giovanna is depicted in strict profile, surrounded by some of her personal possessions. The pendant hanging from her slender neck and the luxurious brooch lying on the shelf would have been the jewellery she received from the Tornaboeni family as wedding gifts and allude to her public life and high social status. Besides depicting her elegant, idealised bearing, Ghirlandaio also conveys the young woman’s spiritual depth, in keeping with the Neoplatonic ideal of physical and spiritual beauty then in vogue. For this purpose, he painted the cartellino displaying a variant of one of Martial’s epigrams (XXXII) and a small book lying on the shelf. It is a libriccino da donna, whose canticles were used by women to guide their prayers throughout the day. These books of hours for private devotion were luxury items and many of them were commissioned on the occasion of weddings. The texts were illustrated with exquisite images and scenes that headed the calendars and cycles of prayers and sometimes included the coat of arms of the family who commissioned them. In accordance with the tastes of the great Florentine families such as the Medici, these manuscripts were usually protected by a luxurious cover decorated with precious metals and other sumptuous materials.

The Virgin of the Annunciation / The Angel of the Annunciation (recto)

Bernhard Strigel was an important German painter of the late 1400s and early 1500s and his work shows the influence of other prominent artists of the period such as Dürer and Dieric Bouts. These two panels must have been part of a larger ensemble. The influence of Flemish art is evident in the elongated proportions of the figures. The artist presents the theme of the Annunciation according to the Gospel of St Luke (1: 26–38).

In the scene the angel appears to the Virgin in a simple room with a window looking out onto a landscape in the centre. Mary is positioned on the left of the composition and her gaze, the position of her hands, and modest attitude evidence her acceptance of the divine message. The dove of the Holy Spirit descends on her. Here – unlike in other Annunciations in the Museum’s collection such as that of Jan van Eyck – the painter portrays her sitting at a desk before an open book: the Holy Scriptures. Once again we find an image of the Virgin reading with a double meaning: it emphasises Mary’s piety and devotion, but also her capability and excellent intellectual grounding. There are literary and artistic testimonies of this theme dating from the Carolingian period onwards.

Portrait of a Lady

The image of a woman reading or holding a book, as in this painting by Pier Francesco Foschi, enjoyed success in the history of painting from the Renaissance onwards, when portraiture became a genre in its own right without religious connotations. Nothing is known about the identity of the attractive sitter or her pursuits, tastes and thoughts. However, the canvas reveals aspects of her character and life that bring to mind Florentine high society, to which she almost certainly belonged.

The young lady is very elegantly dressed and poses for the spectator in an architectural setting whose plainness and muted colours perfectly set off her beauty and clothing. The painter avoids including any features that might distract the spectator’s attention from the figure, which is stylised and exquisite in all aspects.

In her right hand the lady holds a small book she is halfway through reading, and marks the page with her index finger in order to shortly resume her activity. Her lowered, and engrossed gaze indicates she has stopped to reflect on the text which held her attention until a few minutes ago. The smallness of the book – which could be described as pocket size – allows it to be carried around and read anywhere. It is a prized object the artist has placed in the sitter’s hands to attest to and stress the sitter’s intellectual qualities, but also to draw attention to his client’s pursuits during a moment of leisure in which the pleasure of reading would have played a special role.

Portrait of a Woman with a Dog

Veronese is one of the great artists who, together with Titian and Tintoretto, revolutionised 16th-century painting and created the so-called Venetian School of painting, which went on to influence all subsequent art. A highly skilled colourist, he produced above all religious and mythological paintings, though he also devoted part of his output to portraiture.

This lady, whose identity is unknown, is portrayed in a three-quarter pose gazing leftwards and accompanied by a small dog. Veronese describes the different textures of the rich blue and white fabrics of her clothing with absolute mastery. With a finger she points to the page where she has stopped reading the book she holds, from which hang two small loops to fasten it.

After Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press around 1450, the publication of books developed considerably in Venice, where high-quality examples were produced in various formats. As a novelty pocketsized books – previously reserved for devotional texts – began to come out, which were portable and could be read anywhere. Classical Greco-Latin and pastoral literature was in vogue during the period. It discussed the different kinds of love, usually in the form of dialogues, and described courting scenes that took place in bucolic places far from the city.

Portraits of people reading, characteristic of Venetian Cinquecento painting, mostly featured men, though sometimes women were also portrayed with books. Paintings of the belle donne veneziene – possibly images of idealised, sensual ladies – coexist alongside intimate portraits of these women reading or simply posing with a book in their hands. Their faces and gestures denote a certain melancholy and self-absorption.

The Annunciation

This annunciation has been attributed to Gentile Bellini and is dated to about 1475. The artist has chosen to set the episode in a street in a completely empty city where the message is delivered outside the grand Renaissance portico in whose interior Mary kneels. Beneath the portico is a book lying on a lightweight folding portable lectern. In western art the Virgin is depicted busy reading the Holy Scriptures, whereas Oriental art traditionally shows her engaged in domestic chores such as fetching water from the well or weaving a purple veil for the temple.

In western art the Virgin is depicted busy reading the Holy Scriptures, whereas Oriental art traditionally shows her engaged in domestic chores such as fetching water from the well or weaving a purple veil for the temple.

The Gospel of St Luke (1: 26–38), which records the event, does not provide much information about the angel’s greeting, except that it took place in Galilee, in the city of Nazareth. Artists had to turn to complementary sources or their imagination to visualise this moment in Mary’s life. The book the Virgin is reading and meditating on, a symbol par excellence of knowledge and erudition, has always been identified as a religious work such as a psalter – a collection of psalms which constituted the corpus of prayers most widely disseminated among laypeople – or a later book of hours. Artists were not overly concerned about making clear what it was Mary was poring over, they were interested simply in the fact that she was reading and the connotations this act held for the spectator or believer.

There is also a glimmer of a courtly gesture in the position of the angel with one knee on the ground. This archangel holds a stalk of lilies, which in traditional northern European painting is commonly depicted in a vase visible in the setting where the Annunciation takes place.

The Annunciation

Jan de Beer sets his annunciation in a Flemish bourgeois interior, an environment his contemporaries would have considered highly suitable on account of its familiarity. The panel, which forms a pair with The Birth of the Virgin, features the three essential figures: the Virgin, the angel and the dove of the Holy Spirit. Once again Mary is depicted before an open book, in this case medium-sized, which needs to be supported by a solid cabinet containing two other hardcover books with fine leather bindings.

The book Mary is reading, which has two elegant gilt clasps, lies on a green velvet cloth. There is every indication it is a sacred book that has been given a cloth covering to prevent the reader’s hands from touching it, as a sign of respect. The cushions decorating the room and the sewing bag, all of which display the letters of Christ’s monogram in gilt embroidery on the front, are made of the same green velvet.

Once again the Virgin is presented to the faithful as a cultured woman who reads out of devotion and in a scene where the book emphasises her religious and intellectual concerns. The artist includes the text of the greeting on the ribbon scrolls positioned between the figures to stress not only the dialogue between them but also the message. Jan de Beer extends the discourse to other corners of the room such as the top shelf, from which a sheet of paper is about to gently tumble down, and the neatly rolled up scroll leaning on the wall beside it. Another episode in Mary’s life, which takes place after the Annunciation and the Incarnation, is depicted outside the room: the Visitation.

The Annunciation

Dated to around 1576, before El Greco settled in Spain permanently, this painting, strongly influenced by Venetian art, sums up the guidelines established by the Council of Trent; among them representing the Annunciation with due majesty and greatness as the episode prior to the Incarnation of Christ.

To restore the Annunciation to its rightful magnificence, the Council decreed that artists should avoid the excessively familiar and ordinary settings in which it had been depicted in the past and required them to focus on the supernatural aspect.

From this point onwards Saint Gabriel was to be shown visiting Mary on a cloud and accompanied by a choir of angels in order to imbue the message with greater glory. The image of Mary as a cultured and pious person, however, remained unchanged. The book continued to be an important feature of Annunciation scenes because, according to Saint Bernard, it recalls the prophecy of Isiah (7: 14): ‘Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel’. According to the same source, if the book is closed, it is linked to this prophet’s words (29: 11–12): ‘The whole vision has become to you like the words of a book that is sealed, which men deliver to one who is literate’.

Adapting the post-Tridentine canons, El Greco shows the angel, who recalls the painting of Veronese with his solemn gesture and pose, grasping a sceptre. Mary, facing the spectator with her head turned, holds one hand to her heart and rests the other on the text she is reading, while the dove of the Holy Spirit emerges from a parting of the heavens to stress the Incarnation and its doctrinal importance.

Portrait of a Woman aged Fifty-six

Cornelis Ketel was a prominent Dutch painter of the late 16th century. As was customary in his period, he specialised in portraits, both group and individual. Although he also painted allegorical and narrative scenes, he attained his height of artistic development in this genre. He shunned the traditional canons and introduced innovations that laid the groundwork for the great masters of the following century such as Frans Hals and Thomas de Keyser.

Here Ketel depicts the sitter against a dark background with her face turned towards, and gazing at, the viewer, experimenting with her body and pose. Her body fills almost the entire picture space and is rendered in a palette of browns and dark colours. The artist concentrates on studying her face and hands, one of which holds a book. Portraying women reading – in this case possibly a religious text – was a means of indicating piety as well as education and even a certain social status. In this work the woman marks the page she is on with her finger.

These depictions of women holding a book were common in Dutch painting of the 16th and 17th centuries. The Rijksmuseum houses another example by Pieter Pietersz. entitled Portrait of Dirckje Tymansdr Gael, called van der Graft, Wife of Mattheus Augustijnsz Steyn where the sitter is also shown with a book, pointing to the page. The humanist discourse on marriage and the family spread to northern scholars such as Erasmus and Vives in the 16th century. Dutch printers brought out many new books on marriage, raising children, administering the household, etiquette and education.

Continues on the fisrt floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Portrait of Helena de Kay

Helena de Kay, the woman depicted in this small panel, was a painter, illustrator and cultural promoter in New York in the second half of the 1800s.

Around 1872 her brother, the art critic Charles de Kay, introduced her to Winslow Homer who, like her, painted and studied in the Tenth Street Studio Building. It was probably in this legendary building used exclusively by artists where Homer painted his friend’s portrait.

The inscription on the skirting board depicted in the painting refers to another date, however: 3 June 1874. This was the day Helena de Kay married the writer and publisher Richard Watson Gilder, whom she had also met in 1872. To mark the event Homer gave this painting to the sitter, who kept it her whole life.

The sober image of Helena de Kay is accompanied by two elements steeped in symbolism: the red rose, stripped of its petals lying on the floor, and the book in her hands. The rose is probably a reference to flower painting, the genre De Kay practised as an artist. The fallen petals can also be interpreted as a possible lost love between her and Homer. After marrying, Helena de Key stopped exhibiting her work publicly, though she continued with her illustrations, translations and cultural activities through the foundation of the Art Students League and the Society of American Artists and the Friday gatherings at the family home.

Aside from De Kay’s specific connections with the literary world through her family and friendships, books are a recur- ring element in female portraits of this period in which reading was associated with escapism. The closed book, which occupies a central role as the tip of the triangle it forms with the head and the flower, also has significant evocative power as it refers to what happens before or after it is read. With her head hanging but eyes open, here De Kay seems to be engrossed in her thoughts – who knows if they are related to the contents of the book, whose title is unknown, or to the many events linked to this portrait.

A Girl in Japanese Gown. The Kimono

A woman has just closed a folder. She pauses to rest, as if reflecting on what she has been looking at up until a few seconds ago. A magazine stand and a few sheets of paper scattered on the floor attest to the activity preceding this moment of calm.

In this painting of a woman the American artist William Merritt Chase illustrates the craze for things Japanese during the last third of the 1800s. The artist, as if a voyeur, has penetrated into this dark, intimate scene where a woman dressed in Oriental style has been contemplating what appear to be Japanese drawings or prints.

Following the opening up of Japan and the expansion of the trade routes in the mid-19th century, Japonisme immediately spread across Europe and America. As a representative of the Impressionist school in the United States and influenced by James McNeill Whistler, who provided American artists with a European connection.

Chase adopted a few compositional features characteristic of Japanese prints and certain elements of Oriental styles, such as the upward perspective and asymmetry of the composition. Chase also became a keen collector of objects from Asian cultures, some of which he included in his own works from the 1880s onwards. Some of these pieces are recognisable in A Girl in Japanese Gown. The Kimono, which belongs to a series of ‘kimono portraits’ the American artist painted of a few relatives and friends.

Hotel Room

Edward Hopper started out as a member of the so-called American Scene, a group of artists who shared an interest in American subjects, but very soon developed his own style of melancholic, simplIfied depictions of contemporary reality. In 1924 he married Jo Nivinson, who posed as a model for many of his compositions and kept a detailed record of the painter’s works throughout her lifetime.

In 1931 Jo sat for the taciturn female figure in Hotel Room. Hopper painted her at the lowest point of the Great Depression, which, for him, symbolised the crisis of modern life. The painting is the first in a long series of works picturing solitary figures in interiors in different hotels and bars. In all of them Hopper’s realism, a combination of trueness to life and a powerfully moving quality, transforms what might otherwise be simple scenes of daily life in- to metaphors of loneliness and frustration. Its narrative nature so characteristic of his work leads us to imagine what could have happened to this solitary semi- naked young woman in a stark hotel room in the middle of the night. Perhaps she has just arrived and has taken off her hat, dress and shoes and, not yet having unpacked, has sat down languidly on the edge of the bed to read a yellowed sheet of paper with the introspection typical of the female figures in Hopper’s paintings. We know from Jo’s exhaustive notes that it is a train timetable; this leads us to wonder why this solitary, modern woman has decided to travel. Could she have decided to flee and start a new life?

Hopper accentuates the dramatic effect of the scene by means of electric lighting, which creates powerful contrasts of lights and shadows. The angle of vision and upward perspective with marked diagonals directs our gaze towards the background, where a half-open window reveals the pitch blackness of the night – a symbol of the uncertainty hovering over the woman.

Continues on the ground floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

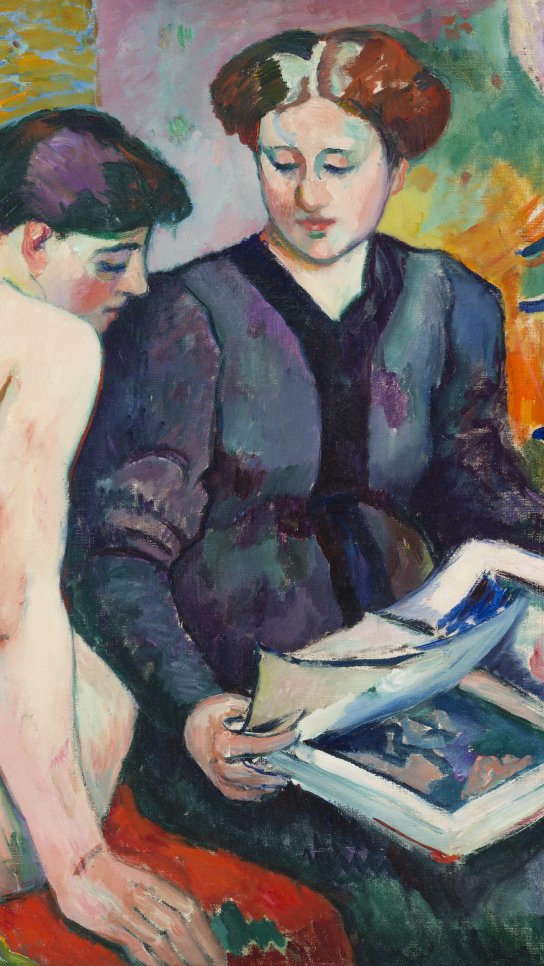

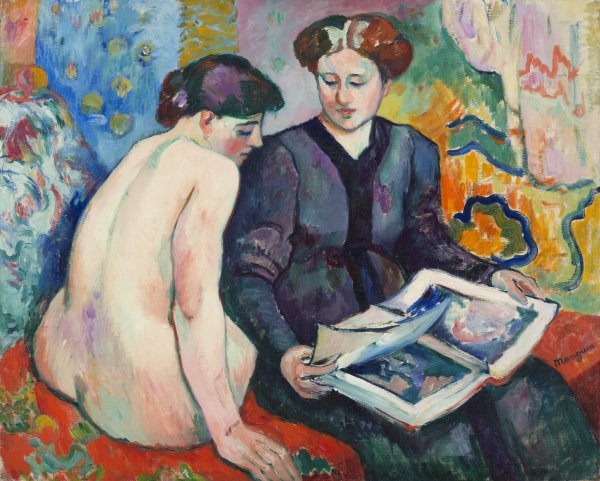

The Prints

Jeanne-Marie Carette became the French painter Henri Manguin’s favourite model in 1899, the year they married. In the garden of their marital home on the Rue Boursault in Paris they built a studio with removable panels where their sitting sessions took place for more than thirty years.

Jeanne plays a double role in The Prints, executed six years after their wedding. She is depicted naked on the left with her back to the viewer but also on the right, clothed and positioned frontally.

As the title indicates, a book of prints is the focal point of this complex composition, one of Manguin’s most ambitious works. The two figures, sitting opposite each other on what appears to be a couch or a narrow bed, turn to gaze at the prints held by the clothed one. Here the painter, who depicts his wife reading in other works, shows both versions of Jeanne engrossed in analysing what could be some colour lithographs. Scholars have even argued that the left-hand image might be a metaphor of the importance of the genre of the nude in prints during the period. It has also been suggested that Manguin might be alluding to Ambroise Vollard and his active work as a publisher of series of lithographs. Indeed, the gallery owner became the first owner of this work in March 1906.

The Prints belongs to the French tradi- tion, begun by Delacroix, of depicting seated women in an indoor setting. It displays noticeable traces of Manguin’s relationship with Henri Matisse, his friend since his formative years and subsequently his travelling companion during his foray into Fauvism. A further influence is the discovery of the work of Ingres – who proved to be a revelation for both – which is evident in the composition of the nude with her back to the viewer.

Simone

Georges D’Espagnat became established as a painter in turn-of-the-century Postimpressionist Paris, where he promoted the creation of independent salons and showed his work alongside that of Bonnard and Matisse.

Besides admiring Renoir, the Impressionist master he knew personally, he was interested in the compositions of Old Masters such as Titian, Tintoretto, Rubens and Delacroix and frequented the company of contemporary Symbolist writers.

This canvas stems from the illustrations he made in 1906 for the collection of poems by Rémy de Gourmont, Simone. Poème champêtre. The sobriety of the illustration accompanying ‘Le Houx’ (Holly), one of the poems in which Simone is the common thread, contrasts with this painted version he produced the following year, in which the warmth and exuberance of the colour inundate the scene. The main motif is not, however, the holly, pansies, hyacinths and stocks mentioned in the poem but the figure of the woman who holds and gazes at an open book on her lap, carefully framed by the window, vases of flowers and mountains flanking the bench.

Outdoor leisure activities, such as reading in a park or garden, became a favourite subject for Impressionist and Postimpressionist painters. The woman is shown at a moment of self-reflection, enjoyment or amusement, engaged in an everyday act that was becoming accessible to more people and social classes. Apparently oblivious to her idyllic surroundings, Simone is absorbed in the book, whose title is not visible. This establishes a sort of secret between the object and the girl that shrouds the scene in a certain amount of mystery.

An Autumn Evening

Henri-Eugène Le Sidaner, who was born in the French colony of Mauritius, trained as a painter in Paris, but produced much of his early work from his retreat in the small port of Étaples, near Calais, under the influence of the Impressionists and Postimpressionists.

In 1894 he returned to Paris during the height of the Symbolist trends and painted An Autumn Evening there the following year.

The diffuse light, soft colours and intimate sentimentalism of the scene can be linked to the new Symbolism, whereas the style of execution vaguely recalls Seurat’s Pointillism. However, as can be seen in this composition, Le Sidaner did not espouse the Symbolists’ interest in literature and remained faithful to landscape painting.

In this rural landscape a stone valley crosses the composition from side to side and divides the painting into two. Behind the wall a group of houses and a row of trees are bathed in the soft light characteristic of winter. In front of the wall a woman strolls alone holding a book. Amid the peace and quiet conveyed by the scene, the girl enjoys a moment of solitude, engrossed in reading.

Tour resources

The order of the works in this pdf may differ from the recommended order.